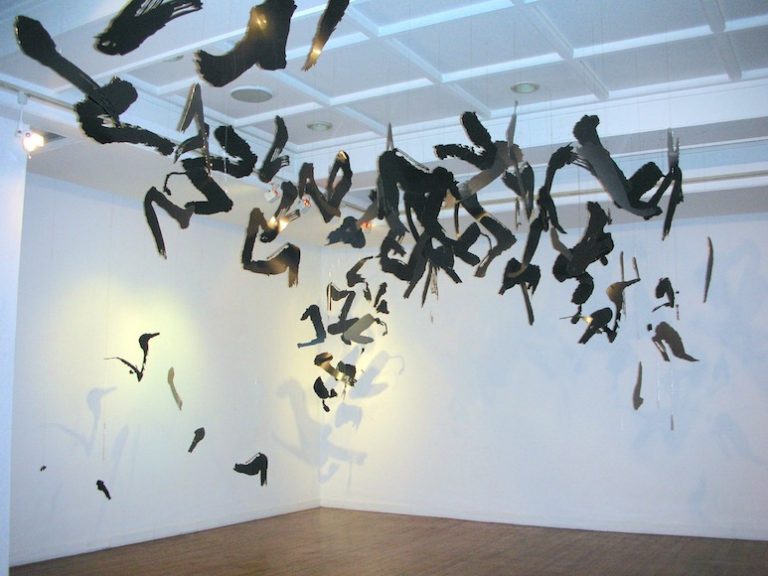

Central House of Artists Museum, Moscow

Installation view

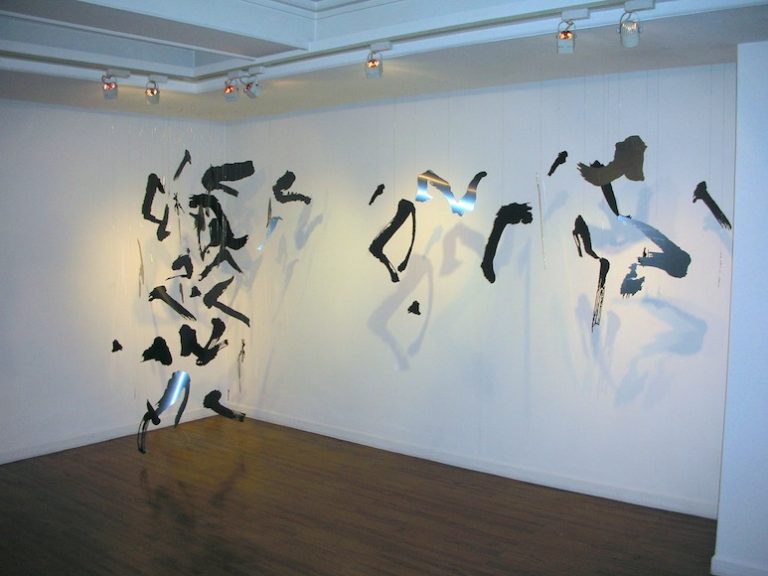

Central House of Artists Museum, Moscow

Installation view

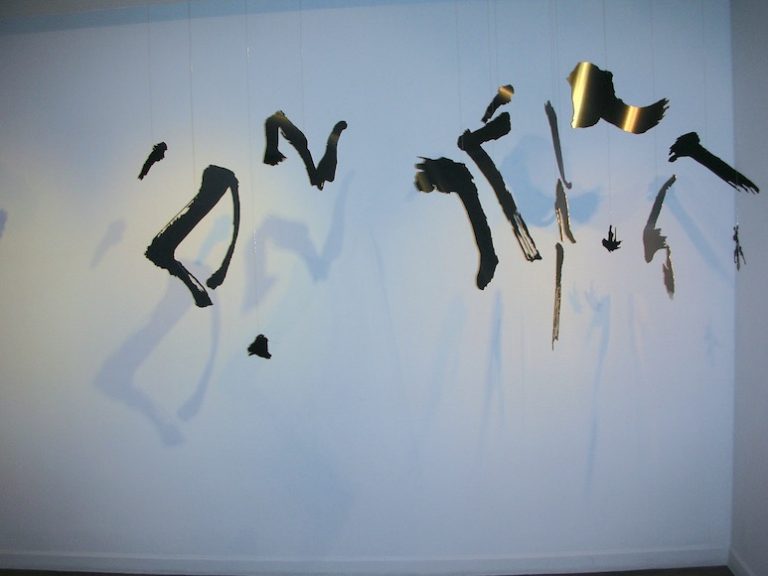

Central House of Artists Museum, Moscow

Installation view

Central House of Artists Museum, Moscow

Installation view

Central House of Artists Museum, Moscow

Installation view

Central House of Artists Museum, Moscow

Installation view

Central House of Artists Museum, Moscow

Installation view

Central House of Artists Museum, Moscow

Installation view

Center for Architecture and Design, Mexico City

Installation view

Center for Architecture and Design, Mexico City

Installation view

Center for Architecture and Design, Mexico City

Installation view

ZONE: Chelsea Center for the Arts is pleased to present “Writing in the Void,” a mobile of 280 calligraphic marks forged in black and silver aluminum by artist Yooah Park. Organized by ZONE: Chelsea, the exhibition will be held at the Central House of Artists Museum in Moscow, and travel to the Center for Architecture and Design, Mexico City (Aug. 10-Sept. 4).

Trained as a brush painter, Yooah Park explores gestural dynamics in painting and sculpture, combining influences from traditional Korean calligraphy artists, and Western artists such as Franz Kline, Agnes Martin, Brice Marden and Alexander Calder.

While Western philosophies typically depict the Void as an infinite absence, the Eastern notion of the Void is frequently described as a “formless field” inexplicably acting as the source and sustenance of all creation. In ancient Korean painting, the artist asserts, negative space is more important than positive space, presumably because of its “pre-rational” shaping intelligence. Following this logic, Park has activated and magnified this dynamism by setting her marks in three-dimensional space, mirroring the guided improvisation of John Cage’s chance techniques.

Perpetual motion also conveys the Buddhist belief in spirits inhabiting inanimate objects. Park’s figures cluster together in groups or stand in isolation as human figures do. And since the figures resemble fragments of ideograms, their suspension suggests a primordial arena wherein a language is first coalescing. This suspension reinforces the minimalist esthetic, the slowing down of time, and the sharpening focus – “the mental suspension, not a mental diversion” – experienced in meditation, as noted by Mark Levy in The Void in Art.

In the past, Park’s organic minimalism has employed multiples, such as her shifting grid of 63 ceramic cubes presented at ZONE: Chelsea in 2004. Always evident are her intimate calligraphic marks, which also adorned her chamber of hand-made tiles denoting Korean funeral ritual and the shedding of esthetic identities in “Rite of Passage” at the Gana Insa art Center in 2002. In April 2006, Park’s mobile installation appeared in a group exhibition at the Dong San Bang Gallery in Seoul.

The Central House of Artists Museum is located at 119049 Krymski val 10 exhibition hall #6, Moscow, Russia.

ZONE: Chelsea would like to thank CHA Director Vasily Vladimirovich Bychkov and Senior manager of the exhibition organizing deparment Marina Milishnikova.

Yooah Park

Writing in the Void

June 28 – July 3, 2006, Moscow

The Central House of Artists Museum

119049 Krymski Val 10 exhibition hall #16, Moscow, Russia

August 10 – September 4, 2006, Mexico

Galeria Emilia Cohen

Juan Vazquez de Mella No. 481, Col. Los Morales Polanco

Mexico D.F.C.P. 11510

I am pleased to present “Writing in the Void”, a mobile of 280 calligraphic marks forged in black and silver aluminum by artist Yooah Park. Organized by ZONE SATELLITE, a division at ZONE:Chelsea, Center for the Arts, the exhibition will be held at the Central House of Artists Museum in Moscow (June 28- July 3, 2006) and will travel to the Center for Architecture and Design, Mexico City (Aug 10 – Sep 4,2006).

Trained as a brush painter, Yooah Park explores gestural dynamics in painting and sculpture, combining influences from traditional Korean calligraphy artists, and Western artists such as Franz Kline, Agnes Martin, Brice Marden and Alexander Calder.

While Western philosophies typically depict the Void as an infinite absence, the Eastern notion of the Void is frequently described as a “formless field” inexplicably acting as the source and sustenance of all creation. In ancient Korean painting, the artist asserts, negative space is more important than positive space, presumably because of its “pre-rational” shaping intelligence. Following this logic, Park has activated and magnified this dynamism by setting her marks in three-dimensional space, mirroring the guided improvisation of John Cage’s chance techniques.

Perpetual motion also conveys the Buddhist belief in spirits inhabiting inanimate objects. Park’s figures cluster together in groups or stand in isolation as human figures do. And since the figures resemble fragments of ideograms, their suspension suggests a primordial arena wherein a language is first coalescing. This suspension reinforces the minimalist esthetic, the slowing down of time, and the sharpening focus ‘The mental suspension, not a mental diversion” experienced in meditation, as noted by Mark Levy in The Void in Art.

In the past, Park’s organic minimalism has employed multiples, such as her shifting grid of 63 ceramic cubes presented at ZONE: Chelsea, Center for the Arts in 2004. Always evident are her intimate calligraphic marks, which also adorned her chamber of hand-made tiles denoting Korean funeral ritual and the shedding of esthetic identities in “Rite of Passage” at the Gana lnsa Art Center in 2002. In April 2006, Park’s mobile installation appeared in a group exhibition at the Dong San Bang Gallery in Seoul.

I would like to thank Director Vasily Vladimirovich Bychkov and Marina Milishnikova, Senior Manager of the Exhibition Organizing Department at Cental House of Artists in Moscow. I would also like to thank Consul General Ramon Xilolt, Karina Escamilla, Program Coordinator at Mexican Cultural Institute of New York, Emilia Cohen, Director of Emilia Cohen Collection and Center for Architecture and Design in Mexico City. Special thanks to Erika Vilfort and Beatrize Ezban for their initial efforts in facilitating Yooah Paws Mexico exhibition and Kiril Milinishikov for his translations for the Moscow exhibition.

Jennifer Baahng ED.D

Director

ZONE: Chelsea, Center for the Arts

“Tonight he feels the potency of every word: words are only an eye-twitch away from the things they stand for.” —Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow

In his sprawling third novel, Pynchon grasped a tectonic shift in the modern era, as the industrial revolution yielded to the age of information. His international cast of misfits roams the shattered landscape of Europe at the close of World War II, no longer trading black-market cigarettes for weapons, machinery, or other tangible goods, but instead bartering with raw data—documents, patents, and even early computer codes, those ephemeral strings of 1’s and 0’s. One implication of this 1973 masterpiece is that humanity as a species is in danger of drifting from its moorings in the physical world, a condition that has come to pass with the alternate reality of cyberspace (a word that already sounds quaint, though it was coined only 20 years ago in William Gibson’s equally prescient novel, Neuromancer).

Yooah Park works in words as well, her art derived from expressive, calligraphic brushstrokes grounded in those immemorial ideograms first laid down millennia ago in ink on rice paper. Yet her newest work is disembodied; she has dispensed with any supporting surface, leaving her laser-cut steel brushstrokes hanging in midair. But like Pynchon’s “eye-twitch,” they remain beautifully corporeal, images that do double duty as “the things they stand for.”

How did Park arrive at this nexus of ancient symbols and (literally) cutting-edge technology?

One factor, no doubt, is travel, from her native Korea, where she received a degree in Oriental Painting, to graduate study in art history at Harvard and drawing at Columbia University. Another is her exploration of various surfaces as vehicles for her art, which has spanned drawing, painting, and sculpture. In the early nineties Park did a series of drawings that traversed the netherworld between figurative expression and pure abstraction, the form and subject reminiscent of Matisse’s bold dancers. Her images from this period are vibrant—leaping, pirouetting, twisting, and landing forms that spread across five-foot sheets of paper, and crouching, bending, lounging shapes compressed into smaller, one-foot squares. Quick arabesques and spatters of ink breathe life into the figures, and also work entirely as nonobjective form, both contained by and pushing at the boundaries of the paper, compositions that create exquisite tension.

Then came her work on clay tiles—calligraphic flourishes baked into the ash-colored mud, the litheness of her gestures mitigated somewhat by the elegiac gray surface. The stiff brushes she uses leave deeply incised ridges in the wet clay that feel, after being fired in a traditional Korean kiln, like fossils, giving both the image she has inscribed and the idea it conveys a sense of deep time, a shrouded past before the invention of writing, drawing, ink, or paper. Sometimes Park sculpts hexagons from this material: small smoky boxes in rows or scattered on the ground, her brushstrokes like weathered, mysterious inscriptions on tombstones. These shapes revisit her square drawings, retaining their coiled tension between the idea and its expression.

Park’s 2002 installation, Rite of Passage,went even further in this journey through idea and form, eschewing any sense of figuration or ideogram, leaving only walls of ashen tiles and hanging strips of handmade pulp paper to envelope the viewer. This tomblike enclosure returned her to art’s most basic element: a bare surface on which to project one’s imagination. In this case, the idea was writ large—the surface became an environment that at once enclosed and expressed a conscious negation of her earlier tools and techniques. A blank slate, in other words.

Fast-forward to the present. Other artists have hung objects from the ceiling—think of the colorful, playful geometries of Calder’s mobiles and Eva Hesse’s gloppy ropes and distended blobs suspended in mesh bags. More recently, the Spanish artist Jaume Plensa filled a New York gallery with curtains of stainless-steel letters that at a distance overlapped into a shimmering tower of Babel, an incomprehensible jumble of characters; only on closer inspection did it become apparent that the letters spelled out excerpts from the Bible’s Song of Songs.It is the curse of language that letters and words must be joined together to express thought, and that those sentences, paragraphs, and entire books remain intellectual abstractions— symbols—of what they represent.

Park, though, has the advantage over writers (or artists using letter forms) of translating thought and emotion into emphatic form through the bodily gestures of her brushstrokes. This is why the athletic traceries of her earlier drawings and clay pieces feel so alive; like those macho “action painters” the abstract expressionists, the movements of her arms, shoulders, torso—her entire body—come across in her energetic strokes of ink, her forceful scoring of clay. Now she has taken her gestures and removed them from any friction with a ground, be it paper or clay, to exist simply in the air. Cut from dark, shiny steel, these palpable strokes are hung in groups, and work on several layers. First, they are individual shapes, each filled with the verve of the original painted stroke (which is used as a template for the laser). But they also work as a whole, coalescing into various shapes as the viewer walks around and within this fragmented aerie. From some angles they seem a single entity that has burst apart and been frozen in time; from others it is as if they desire to gather together, like filings around a magnet. Always, though, they are physical manifestations of the artist’s search for form—idea, thought, and emotion transformed into a graceful dance.

R.C. Baker is a writer and artist who lives in New York City. His column, Best In Show,appears weekly in the Village Voice.

Related:

Categories: spotlight

Tags: Yooah Park