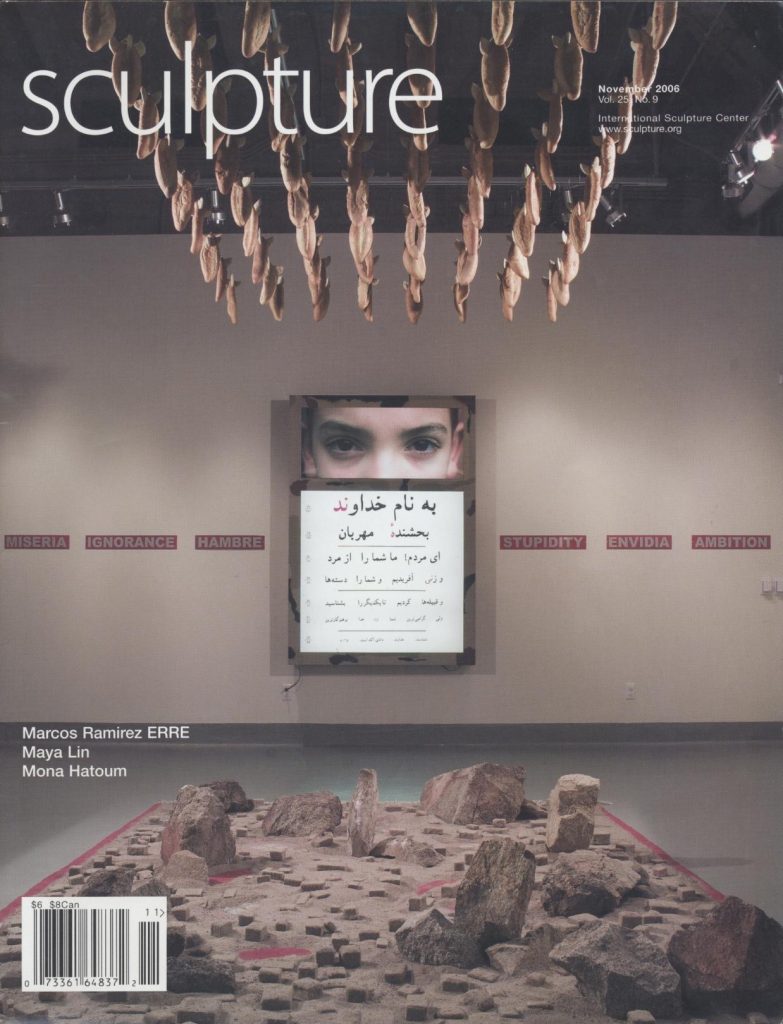

Novbember 2006, Vol.25, P34 - 39, by Howard Risatti

“Jackie Matisse: Collaborations in Art and Science”

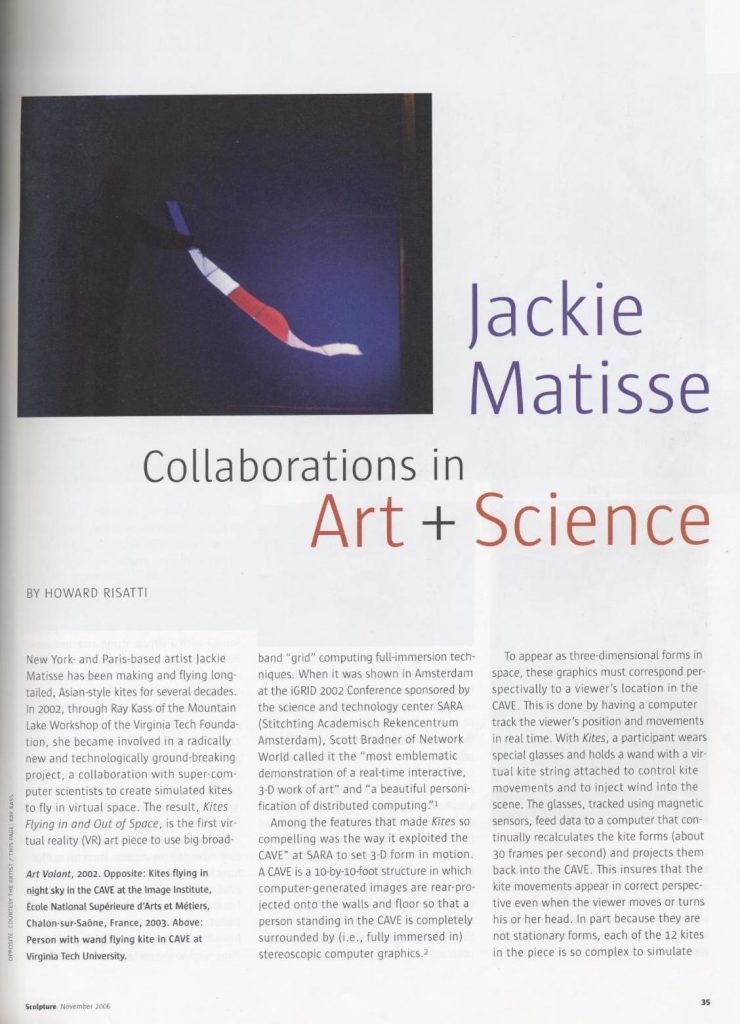

New York and Paris based artist Jackie Matisse has been making and flying long-tailed, Asian-style kites for several decades. In 2002, through Ray Kass of the Mountain Lake Workshop of the Virginia Tech Foundation, she became involved in a radically new and technologically ground-breaking project, a collaboration with super-computer scientists to create simulated kites to fly in virtual space. The result, Kites Flying in and Out of Space, is the first virtual reality (VR) art piece ever created to use big broadband “grid” computing full immersion techniques. When it was shown in Amsterdam at the iGRID 2002 Conference sponsored by science and technology center SARA (Stitchting Academisch Rekencentrum Amsterdam), Scott Bradner of Network World called it the “most emblematic demonstration of a real-time interactive, 3-D work of art” and “a beautiful personification of distributed computing.”1

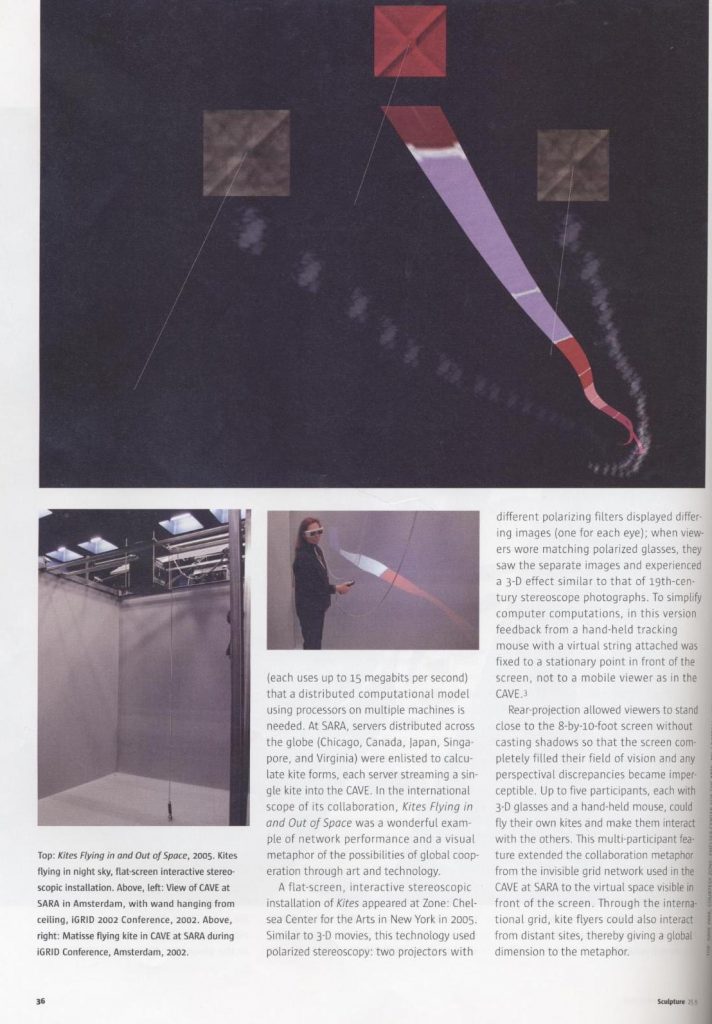

Among the features that made Kitesso compelling was the way it exploited the CAVE™ at SARA to set 3-dimensional form in motion. A CAVE is a 10′ x 10′ structure in which computer-generated images are rear projected onto walls and floor so that a person standing in the CAVE is completely surrounded by (i.e, fully immersed in) stereoscopic computer graphics.2 To appear as three-dimensional forms in space, these graphics must correspond perspectivally to a viewer’s location in the CAVE. This is done by having a computer track the viewer’s position and movements in real time. With Kitesa participant wears special glasses and holds a wand with a virtual kite string attached to control kite movements and to inject wind into the scene. The glasses, tracked using magnetic sensors, feed data to a computer that continually recalculates the kite forms (∼30 frames/second) and projects them back into the CAVE. This insures kite movements appear perspectively correct even when the viewer moves or turns his or her head. In part because they are not stationary forms, each of the 12 kites in the piece is so complex to simulate (each utilizes up to 15 megabits/second) that a distributed computational model using processors on multiple machines is needed. At SARA servers distributed across the globe (Chicago, Canada, Japan, Singapore, and Virginia) were enlisted to calculate kite forms, each server streaming a single kite into the CAVE. In the international scope of its collaboration Kites Flying in and Out of Spacewas a wonderful example of network performance and a visual metaphor of the possibilities of global cooperation through art and technology.

A version of Kitesshown in 2005 at Zone: Chelsea Center for the Arts in New York was a flat-screen, interactive stereoscopic installation. Similar to 3-D movies, this technology uses polarized stereoscopy: two projectors with different polarizing filters display differing images (one for each eye); when viewers wear matching polarized glasses they see the separate images and experience a 3-D effect similar to that of 19th-century stereoscope photographs. To simplify computer computations, in this version feed-back from a hand-held tracking mouse with a virtual string attached was fixed to a stationary point in front of the screen, not to a mobile viewer as in the CAVE.3 Rear-projection allowed viewers to stand close to the 8′ x 10′ screen without casting shadows so the screen completely filled their field of vision and any perspectival discrepancies became imperceptible. Up to five participants with 3-D glasses and a hand-held mouse could each fly their own kite and interact with each others kites. This multi-participant feature extended the collaboration metaphor from the invisible grid network used in the CAVE at SARA to the virtual space visible in front of the screen. Through the international grid kite flyers also could have interacted from distant sites thereby giving a global dimension to the metaphor.

To go from flying real-world kites to collaborating with scientist/engineers to fly virtual kites seems a radical transformation for Jackie Matisse of both means and ends. I say radical because collaboration challenges the art world’s insistence on the singularity of artistic production and because computer imaging challenges the art world’s belief in “personal touch” as a sign of creative individuality.4 Collaboration also is a risky move for the artist as well because, when genuine, it means giving up a degree of artistic control and putting personal identity in jeopardy. But, making and flying kites as art is already a departure from mainstream art practice, so much so that the artist risks not being taken seriously. To most people flying kites seems akin to children’s play or simply an attempt to recapture innocence lost. For Jackie Matisse, however, it moves beyond simple adult desires for innocence and purity. Her kites, with their colorful tails as long as 35 to 45 feet, take Alexander Calder’s conception of sculpture as movement and change (rather than mass in place) and infuse it with an animating spirit. That’s why in the early 1970s she and six other artists including Tal Streeter, Curt Asker, and Istevan Bodoczky signed the Art Volant Manifesto (Flying Art Manifesto) declaring that the kite is “a vehicle joining the spirit and the physical…, the kite’s flying line connects the human hand and mind with the elements.”

For Jackie Matisse, kites are a vehicle to play with color, to “draw” lines in the sky and to sculpt the air. As she has said, “my kites play games with the light, hide and seek with the clouds.”5 The term “play,” however, should be understood more in the philosophical sense of an inventive interaction of creative possibilities through chance and a loosening of personal control. This openness to chance as a genuinely collaborative force in her work has its roots in the1950s and 60s, especially in Gesture painting, Earth and Conceptual/Process art, and the ideas of John Cage.

In Gesture painting the mark left on the canvas is a physical manifestation of an action, a two-dimensional trace in paint declaring the artist’s presence in the world. Such works were not pre-planned, but the result of “situations” organized to open the artist to the unexpected so painting would become a path to the new and to self-discovery. Jackie Matisse shares with Gesture painters their openness to chance and the idea of art as a performative act. However, her kite-drawings are 3-dimensional and made, literally, in the vastness of empty space. They leave no physical trace because their lines are not material manifested on a ground, but lines only in the sense in which we would speak of a “bee” line, a direction or motion of an object–real or imagined–in and through space. Thus, the sculptural forms her kites locate in space are unstable and transitory, continually coming into being and, at the same time, continually disappearing into nothingness. If they are to be understood as betraying the artist’s existential presence, it is at best a fleeting, transitory presence existing only as long as the mind can embrace them as object and concept.

In their conceptual and environmental aspects her works also parallel 1960s Earth and Conceptual /Process Art–here I am thinking of Michael Heizer’s motorcycle drawings in the Nevada desert, the airborne sculpture of Otto Piene and Group Zero in Düsseldorf, and the work of Hans Haacke, specifically his 1967 Sky Line. Sky Linewas a series of helium-filled balloons strung on a line like pearls; when it was released in Central Park it floated upwards creating an actual, physical line in the sky whose shape was determined by chance by the breeze, thus diminishing the role of the artist in the work’s final actualization. In doing so Sky Line reflects the ideas of John Cage who, already in the 1950s, tried to free art from individual taste and ego by using chance methods derived from the I Chingto compose music; his solo piano composition 4’33”(sometimes referred to as Silence) has no notes so when David Tudor premiered it in 1954, only the ambient sounds of nature were heard in the open-air concert hall. Cage went on to use chance to make visual art beginning in 1978.6

Jackie Matisse’s work, even more than Haacke’s Sky Line, is influenced by Cage with whom she developed a close friendship through her step-father Marcel Duchamp. Nevertheless, her work remains independently her own because, unlike Haacke or Cage, she never tries to completely relinquish control. Instead, she actively flies her kites and in doing so the sculptural forms drawn in space can be seen as extensions of her presence in the world and reflections of her “wishes and desires.” On the other hand, the movements of her kites are only prompted by her actions, not completely controlled by them–air currents, air resistance, gravity, aerodynamics all play their part in flying her kites with her. In a kind of mutual action and inter-action, the slightest of hand gestures are magnified, but also altered by the forces of nature acting upon the kite. What results is a “give and take” between her hand and the forces of nature. As she has said,

my kites push and pull on the wind….My hand grows longer and longer until I feel I am somehow in contact with that immensity into and out of which all things come and go.

This is clearly a post-Cagean sensibility because, in giving oneself over to the process of flying, one is neither the sole agent nor a passive witness, but a genuine collaborator with and in nature. This makes the sky an arena in which to both act and to be acted upon, not only to allow, but to prompt the un-expected into being.

On a philosophical level Jackie Matisse’s art is a reminder that we are not alone in the world, but a part of it, that our actions reverberate beyond ourselves. This gives her work a certain resonance with the environmental movement and the existential belief in personal responsibility. It also challenges recent Post Structuralist claims that signs lack presence, that they no longer directly connect to lived experience, only to other signs. Encountering nature through the kite is a direct, lived experience, one that helps situate man in that larger world extending beyond the self–after all, when the artist tugs on the kite line, it is nature, in its fullness, that tugs back. This situating of man in the world through direct experience, it seems to me, is the intellectual underpinning of flying kites as an artistic endeavor.

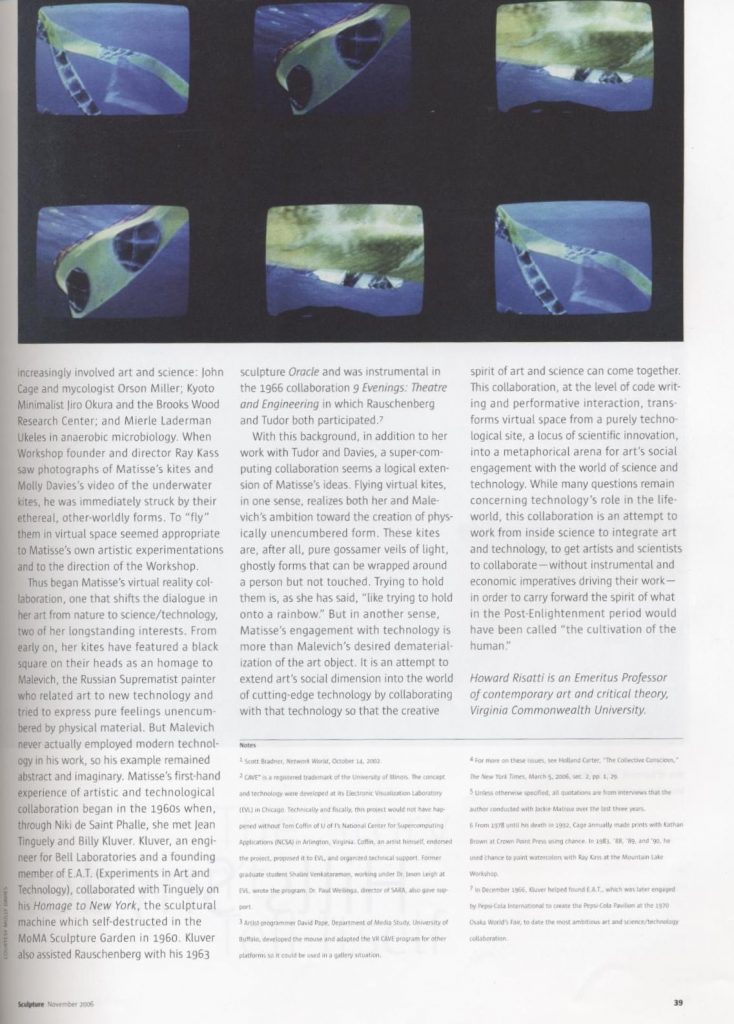

In 1979 when one of her kites accidently fell into the sea, Jackie Matisse got the idea of “flying” kites underwater. This led to collaborations with composer David Tudor and filmmaker Molly Davies in the creation of Sea Tails(a six-monitor, six-channel video installation shown at the Pompidou Center in 1983) and Sound Totem, 9 Lines(a 1986 performance in the Whitney Museum Sculpture Court). These collaborations, which were radically different because now she was not only sharing control with nature but with two other artistic personalities, eventually led to her Mountain Lake Workshop project.

While focus of the Mountain Lake Workshop has always been collaboration, over the years these collaborations have increasingly involved art and science including John Cage and mycologist Orson Miller; Kyoto minimalist Jiro Okura and the Brooks Wood Research Center; and NYC Department of Sanitation “artist-in-residence” Mierle Laderman Ukeles in anaerobic microbiology. When Workshop founder and director Ray Kass saw photographs of Jackie Matisse’s kites and Molly Davies’video of her underwater kites, he was immediately struck by their ethereal, other worldly forms. To “fly” them in virtual space seemed appropriate to her own artistic experimentations and to the direction the Workshop had been going.

Thus began Jackie Matisse’s virtual reality collaboration, one which shifts the dialogue in her art from nature to science/technology, two of her long-standing interests. From early on her kites have featured a black square on their heads as a homage to Malevich, the Russian Suprematist painter who related art to new technology and tried to express pure feelings unencumbered by physical material. But Malevich never actually employed modern technology in his work so his example remained abstract and imaginary. Her first-hand experience of artistic and technological collaboration began in the 1960s when, through Niki de Saint Phalle, she met Jean Tinguely and Billy Kluver. Kluver, an engineer for Bell Laboratories and a founding member of E. A. T. (Experiments in Art and Technology), collaborated with Tinguely on his Homage to New York, that animated sculptural machine which self-destructed in the MoMA Sculpture Garden in 1960. Kluver also assisted Rauschenberg with his 1963 sculpture Oracleand was instrumental in the 1966 collaboration9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering in which Rauschenberg and Tudor both participated.7

With this background plus her work with Tudor and Davies, a super-computing collaboration seems a logical extension of her ideas. Flying virtual kites, in one sense, realized both her and Malevich’s ambitions towards creation of physically unencumbered form; they are, after all, pure gossamer veils of light, ghostly forms that can be wrapped around a person but cannot be touched. Trying to hold them is, as she has said, “like trying to hold onto a rainbow.” But in another sense, her engagement with technology is more than a dematerialization of the art object as Malevich wished. It is an attempt to extend art’s social dimension into the world of cutting-edge technology by collaborating with that technology so the creative spirit of art and science can come together. This collaboration, at the level of code writing and performative interaction, transforms virtual space from a purely technological site, a locus of scientific innovation, into a metaphorical arena for art’s social engagement with the world of science and technology. While many questions remain concerning technology’s role in the life-world, this collaboration is an attempt to work from inside science to integrate art and technology, to get artists and scientists to collaborate–without instrumental and economic imperatives driving their work–in order to carry forward the spirit of what in the Post Enlightenment period would have been called “the cultivation of the human.”

1Scott Bradner, Network World (14 October 2002).

2CAVE™ is a registered trademark of the University of Illinois where the concept and technology were developed at its Electronic Visualization Laboratory (EVL) in Chicago. Technically and fiscally, this project would not have happened without Tom Coffin of the U of I’s National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) in Arlington, VA. Coffin, an artist himself, endorsed the project, proposed it to EVL, and organized technical support. Former graduate student Shalini Venkataraman, working under Dr. Jason Leigh at EVL, wrote the program. Dr. Paul Weilinga, Director of SARA, also gave support.

3Artist-programer David Pape, Department of Media Study, University of Buffalo, developed the mouse and adapted the VR CAVE program for other platforms so it could be used in a gallery situation.

4For more on these issues see Holland Carter, “The Collective Conscious,” The New York Times (5 March 2006), sec. 2, pp. 1 & 29.

5Unless otherwise specified, all quotes are from interviews the author conducted with the artist over the last three years.

6From 1978 until his death in 1992, Cage annually made prints with Kathan Brown at Crown Point Press using chance; in 1983, 88, 89, and 90 he used chance to paint watercolors with Ray Kass at the Mountain Lake Workshop.

7In December of 1966 Kluver helped found E. A. T. which later was engaged by Pepsi-Cola International to create the Pepsi Cola Pavilion at the 1970 Osaka World’s Fair, to date the most ambitious art and science/technology collaboration.

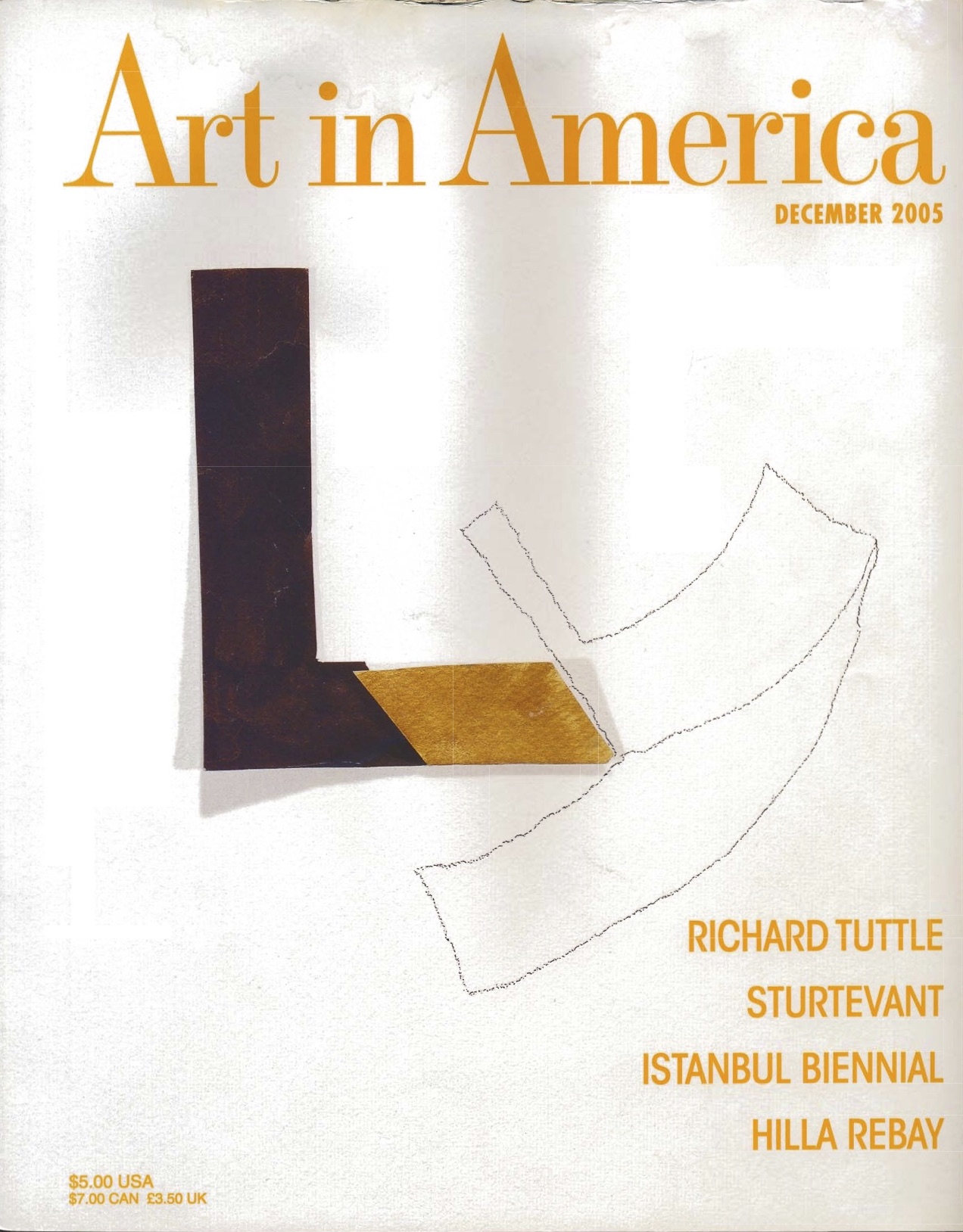

“Airborne Abstraction”, ART IN AMERICA reviews Jackie Matisse’s exhibition

Categories: news

Tags: Jackie Matisse