International artist Zhang Hongtu debuts first solo Midwest show at K-State

The Mariana Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University

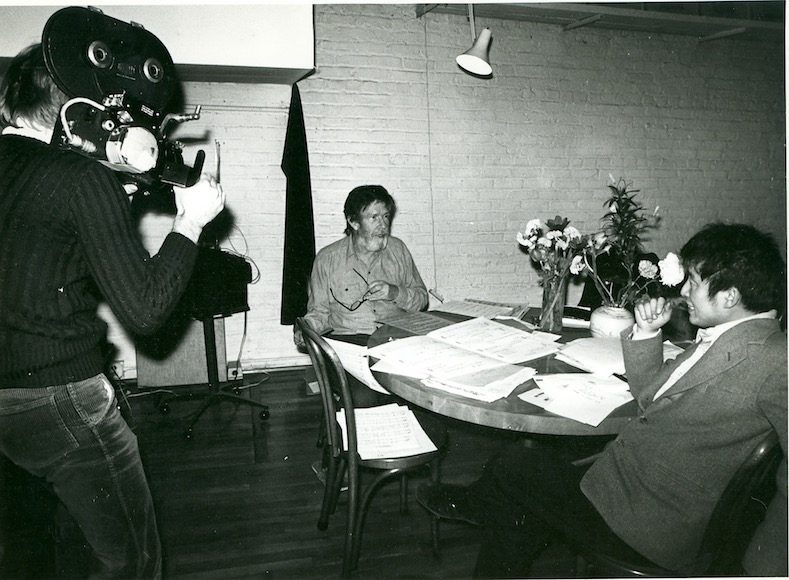

Zhang Hongtu talking about his works

The Mariana Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University

Kansas State University President Richard Myers and Mrs. Myers playing “Ping Pong Mao” by Zhang Hongtu during the exhibition

Courtesy of Kansas State University Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art

The Mariana Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University

Great Wall with Gates III, installation view

The Mariana Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University

“Ping Pong Mao” by Zhang Hongtu in action

Courtesy of Kansas State University Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art

The Mariana Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University

The Mariana Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University

Invitation card

Courtesy of Kansas State University Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art

By Savanna Maude, THE TOPEKA CAPITAL-JOURNAL

September 22, 2018

Zhang Hongtu, an internationally acclaimed artist, will debut his first solo show in the Midwest on Tuesday at Kansas State University.

The exhibition, titled “Culture Mixmaster Zhang Hongtu,” will be installed in the Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art through Dec. 22.

The exhibition brings together early and recent works highlighting Hongtu’s expressions of his hybrid cultural roots.

Hongtu grew up in China as a member of its Muslim minority, suffering persecution for his religion and his political beliefs under the regime of People’s Republic of China founder and Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong.

Hongtu traveled around China as a young artist and was heavily influenced by his study trip to Dunhuang in the western province of Gansu.

Dunhuang was an important stop along the network of trade routes known as the Silk Road, which connected Europe and Africa to the Middle East and Asia. Through the Silk Road, Buddhism traveled from India to China, resulting in the establishment of Buddhist cave temples around Dunhuang between the fourth and 14th centuries. The cave temples featured painting styles different from what Hongtu learned in art school and showed signs of the mural artists’ awareness of European painting.

In 1982, Hongtu moved to New York City to study art.

His works show a lifelong interest in the cycle of travel, immigration, transmission of ideas and cultural cross-pollination.

Included in the exhibit are an oil painting applying the signature style of Vincent van Gogh to a landscape scene from a famous Chinese ink painting, and a Ping Pong table that requires players to avoid letting the ball fall through cutouts in the shape of the head of Chairman Mao.

Hongtu will speak at K-State at the Art in Motion festival on Oct. 6. He also will speak about Buddhist cave temples along the Silk Road on Oct. 9 at the Spencer Museum of Art on the University of Kansas campus.

The Beach Museum of Art is free to the public, and is open from 10 a.m. to 5p.m. Wednesday and Friday, 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. Thursday, and 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Saturday.

SPOTLIGHT

Culture Mixmaster Zhang Hongtu

The Mariana Kistler Beach Museum of Art

Kansas State University

September 25 – December 22, 2018

Zhang Hongtu’s works were shown at his solo exhibition, Culture Mixmaster Zhang Hongtu, at The Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University: September 25 – December 22, 2018.

Internationally acclaimed artist Zhang Hongtu has called many different places home and experienced life as an outsider at different times. Hegrew up in China as a member of the Muslim minority and because of his religious and political backgrounds, suffered persecution during the regime of Chinese Communist Party founder Mao Zedong. In 1982, he moved to New York City to study art and start a new life. This large exhibition, the first solo show of the artist in the Midwest, brings together early and up-to-the-minute recent works highlighting the artist’s endeavors in expressing his hybrid cultural roots.

Zhang’s travels around China as a young artist, most especially his study trip to Dunhuang in the western province of Gansu, proved seminal to his development. Dunhuang was an important stop along the network of trade routes known as the Silk Road, which connected Europe and Africa to the Middle East and Asia. Through the Silk Road, Buddhism traveled from India to China, resulting in the establishment of Buddhist cave temples around Dunhuang between the fourth and fourteenth centuries. The cave temples featured painting styles different from what Zhang had learned in art school and showed signs of the mural artists’ awareness of European painting.Works on display at “Culture Mixmaster” demonstrate Zhang’s lifelong interest in the cycle of travel, immigration, transmission of ideas, and cultural cross-pollination. Included are an oil painting applying the signature style of Vincent van Gogh to a landscape scene from a famous Chinese ink painting, and a ping-pong table that requires players to avoid letting the ball fall through cut-outs in the shape of the head of Chairman Mao.

Major support for this exhibition is provided by a grant from the Greater Manhattan Community Foundation’s Lincoln & Dorothy I. Deihl Community Grant Program, with additional sponsorship by Anderson Bed & Breakfast and Terry and Tara Cupps.

Related:

Categories: news

Tags: Zhang Hongtu

Zhang’s “Mixmaster” exhibit blends his Chinese, American backgrounds

By Megan Moser, The Mercury, Manhattan, Kansas, October 7th, 2018

Zhang Hongtu seemed genuinely excited to be in Manhattan on Wednesday.

The New York City-based artist and his wife, Miaoling, were in the Little Apple for the opening of his exhibition Culture Mixmaster, which is at K-State’s Beach Museum of Art through December. Zhang’s It’s his first solo show in the Midwest.

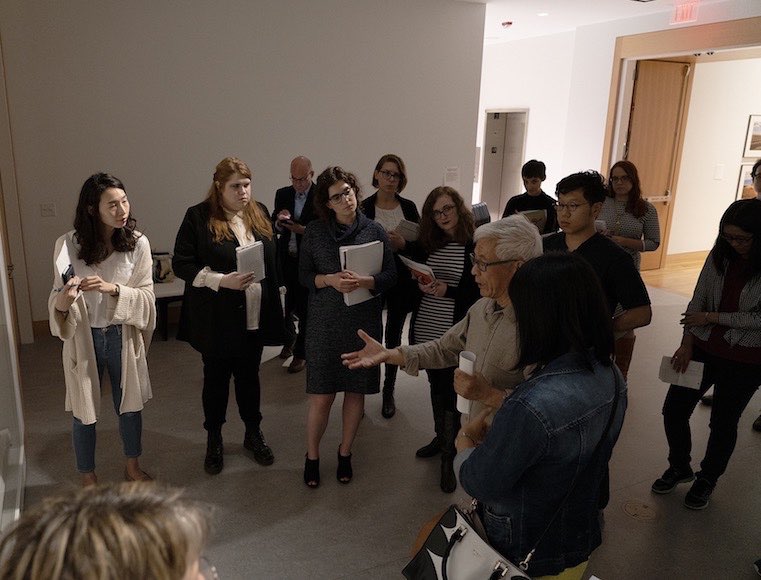

During a preview last week, Zhang, a youthful septuagenarian with white hair and trendy glasses, said he was thrilled with the way the exhibit had turned out.

“With this show, I didn’t come here to see the process of installation,” Zhang said, complimenting the museum’s curators. “It’s beyond my imagination. It’s still my work, but under a different concept of installation, lighting.”

Zhang’s work, like his life, is a blending of the East and the West.

Zhang grew up in China but has lived in America since the 1980s, so he’s now been in the U.S. as long as he had been in China. He likes to say he’s 100-percent Chinese and 100-percent American.

“When you see the show, you’ll see works that mix the tradition from Western European painting with classical Chinese painting,” curator Aileen June Wang said. “And all of his life, Hongtu has been thinking about this question and celebrating the richness of cultural exchange and cultural mixing.”

The pieces on display show a playful combination of influences and represent Zhang’s interest in the effects of travel and migration on culture.

The works include classic blue-and-white Chinese ceramics in the distinctive shape of Coke bottles, and a self-portrait that blends the styles of Pablo Picasso and Leonardo DaVinci’s “Mona Lisa.” That portrait was first made on the computer with Photoshop, and printed with an inkjet printer Wang said. Zhang later painted a version of it, so the printed version that’s on display at the Beach is actually the original, she said.

One entire gallery is devoted to a reimagining of Vincent Van Gogh’s 39 portraits as those of the Zen Bodhidharma.

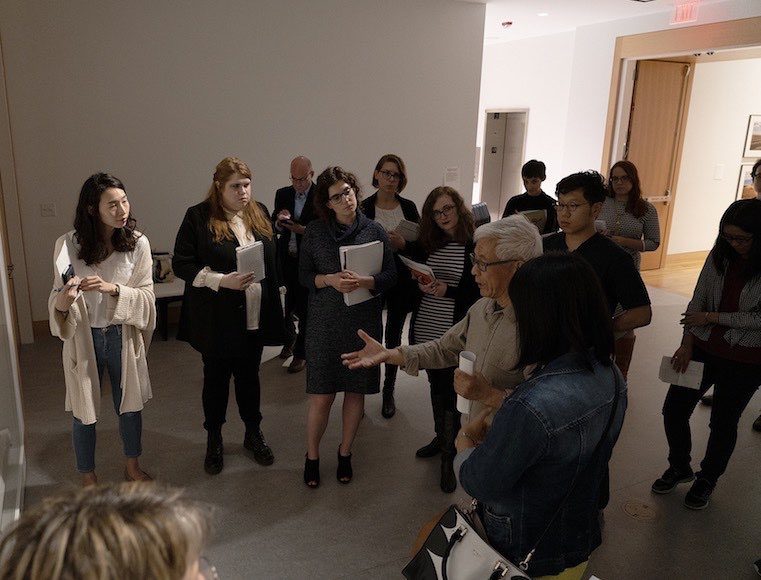

Perhaps the most fun piece is an “interactive sculpture” called “Ping Pong Mao,” a table tennis table whose surface features cutout silhouettes of Chairman Mao Zedong.

On Saturday the museum staged a tournament using the table.

Zhang said the experience of playing on it — and trying to keep the ball from falling through the cutouts — is similar to the experience of living in China after the Cultural Revolution.

“The situation in China is still like this,” Zhang said. “You can criticize someone else, but not political leaders. So nothing changes, politically.”

He mentioned that his wife was a ping-pong champion at her school when she was a girl. Miaoling shook her head furiously, embarrassed by the attention.

Ping pong was an important tool in diplomatic relations between the United States in China in the 1970s. The use of the ping-pong table is another example of east-west culture exchange.

Zhang grew up in China as part of the Muslim minority. Because of his family’s religious and political beliefs, he said they suffered persecution under Mao, and he often felt like an outsider.

His family relocated many times between the Chinese Civil War and the beginning of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. At that time, he saw the political movement as edgy and was eager for change, so he supported it. He began to have doubts, though, when he saw the violence that arose from the revolution. He said he felt he had been fooled by someone he believed in.

He attended art school in China, where anything the students produced had to fit within the narrow scope of communist ideals, and there was a heavy emphasis on depicting Chairman Mao.

After college, Zhang continued to travel and immigrated to the United States in 1982 to find artistic freedom. His wife followed in 1984 with their son. Zhang and his wife now live in Woodside, Queens, a diverse neighborhood where Zhang told The New York Times “I’ve never felt like a foreigner.”

He got early attention for works like his 1989 “Last Banquet,” a version of “The Last Supper” that substitutes 13 Maos for Jesus and his disciples, a work that was part of a Guggenheim exhibit last year. Ironically, that piece was censored, though Zhang said.

Though he hasn’t lived in China for 30 years, Zhang said his view of China is still relevant today, as Mao’s influence persists. That said, he moved away from using Mao’s likeness in the 1990s.

Certainly the most attention-grabbing piece in the exhibition is the 45-by-12-foot “Great Wall with Gates III.”

Zhang made the first version of that work in 2009 for the anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

He made the current version especially for the Beach exhibit. It’s a digital image of the Great Wall of China altered with Photoshop to include a number of gates.

“I used the Great Wall not only about China, but basically about walls. Walls always divide, always stop people (from) going through,” he said. “I picked the image of the wall but with many many gates to change the function of the wall. Make it playful, not to block anymore.”

The exhibit’s title wall features a reproduction of a painting called Two Monkeys. Beach Museum curator Aileen June Wang said she asked Zhang whether the monkeys in the painting represented him, and he handed her a card that said, “You can ask me anything except about the monkeys,” she recalled, laughing.

But Wang said she and museum director Linda Duke have a theory. In Chinese literature there is a classic called “Journey to the West” about the adventures of a monkey god who accompanies a Chinese monk as he travels to India to get sutras and bring them back to China to contribute to the study of Buddhism.

“The journey of that monkey god is similar, or Hongtu feels some affinity, to the adventures of that character,” Wang said. Zhang smiled as she explained this but neither confirmed nor denied the hypothesis.

Artist talk by Zhang Hongtu

5 p.m. Tuesday

Zhang will share his experience of traveling to Dunhuang in western China, a town known as a hub of cultural exchange connecting Europe and Asia.

Related:

Categories: news

Tags: Zhang Hongtu

Zhang Hongtu at The Mariana Kistler Beach Museum of Art

The Mariana Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University

Zhang Hongtu talking about his works

The Mariana Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University

Kansas State University President Richard Myers and Mrs. Myers playing “Ping Pong Mao” by Zhang Hongtu during the exhibition

Courtesy of Kansas State University Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art

The Mariana Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University

Great Wall with Gates III, installation view

The Mariana Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University

“Ping Pong Mao” by Zhang Hongtu in action

Courtesy of Kansas State University Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art

The Mariana Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University

The Mariana Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University

Invitation card

Courtesy of Kansas State University Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art

Zhang Hongtu’s works were shown at his solo exhibition, Culture Mixmaster Zhang Hongtu, at The Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University: September 25 – December 22, 2018.

Press Release at the Beach Museum of Art.

Internationally acclaimed artist Zhang Hongtu has called many different places home and experienced life as an outsider at different times. Hegrew up in China as a member of the Muslim minority and because of his religious and political backgrounds, suffered persecution during the regime of Chinese Communist Party founder Mao Zedong. In 1982, he moved to New York City to study art and start a new life. This large exhibition, the first solo show of the artist in the Midwest, brings together early and up-to-the-minute recent works highlighting the artist’s endeavors in expressing his hybrid cultural roots.

Zhang’s travels around China as a young artist, most especially his study trip to Dunhuang in the western province of Gansu, proved seminal to his development. Dunhuang was an important stop along the network of trade routes known as the Silk Road, which connected Europe and Africa to the Middle East and Asia. Through the Silk Road, Buddhism traveled from India to China, resulting in the establishment of Buddhist cave temples around Dunhuang between the fourth and fourteenth centuries. The cave temples featured painting styles different from what Zhang had learned in art school and showed signs of the mural artists’ awareness of European painting.Works on display at “Culture Mixmaster” demonstrate Zhang’s lifelong interest in the cycle of travel, immigration, transmission of ideas, and cultural cross-pollination. Included are an oil painting applying the signature style of Vincent van Gogh to a landscape scene from a famous Chinese ink painting, and a ping-pong table that requires players to avoid letting the ball fall through cut-outs in the shape of the head of Chairman Mao.

Major support for this exhibition is provided by a grant from the Greater Manhattan Community Foundation’s Lincoln & Dorothy I. Deihl Community Grant Program, with additional sponsorship by Anderson Bed & Breakfast and Terry and Tara Cupps.

Source: https://beach.k-state.edu/explore/exhibitions/culture-mixmaster.html

Culture Mixmaster Zhang Hongtu

The Mariana Kistler Beach Museum of Art

Kansas State University

September 25 – December 22, 2018

Related

Categories: spotlight

Tags: Zhang Hongtu

The New Yorker on “CAGE NAM JUNE: A Multimedia Friendship”

The New Yorker, Nov.6, 2006, p. 25

“CAGE NAM JUNE: A Multimedia Friendship”

Once, when asked what he would most miss if he dies, John Cage replied, “The conversation with Nam June Paik.” The two met in 1958 at a composers’ festival in Germany and instantly disliked each other’s music, but skepticism grew into a challenging and fertile friendship that lasted thirty-five years. Works by both are presented, including some lovely, simple prints made with aquatint and smoke by Cage and a short video interview with Paik, in which he reminisces about an infamous action in which he interrupted a performance by cutting Cage’s necktie in half.

Through Nov. 3. (ZONE: Chelsea Center for the Arts, 601 W. 26thSt. 212 255 2177.)

Related:

Categories: news

Tags: CAGE NAM JUNE

Time Out New York recommends “CAGE NAM JUNE: A Multimedia Friendship”

Time Out New York, October 19-25, 2006 Issue 577, p. 104

……………………………………………………………………………

ZONE: Chelsea Center for the Arts

……………………………………………………………………………

601 W 26thSt between Eleventh and Twelfth Aves (212-255-2177). Tue-Sat 11am-6pm.

*“Cage Nam June: A Multimedia Friendship”

An exhibition of videos, installations, music, photographs and more celebrating the 35-year association between Nam June Paik and John Cage.

Through Nov 3.

*Recommended

Related:

Categories: news

Tags: CAGE NAM JUNE

Hommage to JOHN CAGE/ NAM JUNE PAIK by Margaret Leng Tan

Hommage to John Cage and Nam June Paik by Margaret Leng Tan

Thursday, October 5th 2006, 7pm

Accompanying the exhibition, CAGE NAM JUNE: A Multimedia Friendship, at the opening night performance on October 5, 7pm, the renowned Cage interpreter, Margaret Leng Tan, celebrate the Cage-Paik legacy with her toy piano/toy instrumental Hommage to John Cage/Nam June Paik.

Program

HOMMAGE to JOHN CAGE/NAM JUNE PAIK

by

MARGARET LENG TAN

toy piano, toy instruments

HOMMAGE to NAM JUNE PAIK (2006) Margaret Leng Tan

(first performance)

SUITE FOR TOY PIANO (1948) John Cage

4′ 33″ (1952) John Cage

from OLD McDONALD’S YELLOW SUBMARINE (2004) Erik Griswold

BICYCLE LEE HOOKER

toy piano, bicycle bell and horn, train whistle

CHOOKS Erik Griswold

toy piano and wood blocks

5’29.75″ FOR SIX TOY PLAYER PIANOS/

Elegy for Nam June (2006) Margaret Leng Tan

(first performance)

STAR-SPANGLED ETUDE #3 (“Furling Banner”) (1996) Raphael Mostel

toy piano, siren, whistle, cap gun

Thursday, October 5th 2006

7pm

Margaret Leng Tan has established herself as a major force within the American avant-garde; a highly visible, talented and visionary pianist whose work sidesteps perceived artificial boundaries within the usual concert experience and creates a new level of communication with listeners. Embracing aspects of theater, choreography, performance and even “props” such as the teapot she “plays” in Alvin Lucier’s Nothing is Real,Tan has brought to the avant-garde, a measure of good old-fashioned showmanship tempered with a disciplinary rigor inherited from her mentor John Cage. This has won Tan acceptance far beyond the norm for performers of avant-garde music, as she is regularly featured at international festivals, records often for adventurous labels such as Mode and New Albion and has appeared on American public television, Lincoln Center and even at Carnegie Hall.

Born in Singapore, Tan was the first woman to earn a doctorate from Juilliard, but youthful restlessness and a desire to explore the crosscurrents between Asian music and that of the West led her to Cage. This sparked an active collaboration between Cage and Tan that lasted from 1981 to his death, during which Tan gained recognition as one of the pre-eminent interpreters of Cage’s piano music, partly through her New Albion recordings, Daughters of the Lonesome Isleand The Perilous Night/Four Walls. After Cage’s death in 1992, she was chosen as the featured performer in a tribute to his memory at the 45th Venice Biennale.

Tan takes a lively interest in the musical potential of unconventional and unlikely instruments, and in 1997 her groundbreaking CD, The Art of the Toy Piano on Point Music/Universal Classics elevated the lowly toy piano to the status of a “real” instrument. Tan is certainly the world’s first, and so far, only professional toy piano virtuoso. Since then her curiosity has extended to other toy instruments as well, substantiating her credo “Poor tools require better skills” (Marcel Duchamp).

Tan favors music that confronts and defies the established boundaries of the piano and her toy instruments and has collaborated with like-minded composers to create works for her, such as Somei Satoh, Tan Dun, Michael Nyman, Julia Wolfe, Toby Twining and Ge Gan-ru; she is also a favorite of composer George Crumb. Tan’s authority on matters of Cage has evolved from that of an expert interpreter to responsible scholar protecting the textual integrity of his work; Tan edited the fourth volume of Cage’s piano music for C. F. Peters and in 2006 gave the premiere of his newly discovered 1944 work Chess Pieces, which she also edited for publication. Tan’s Mode DVD of Cage’s Sonatas and Interludes includes a video in which she examines the original, 1940s era preparation materials for the work. Photogenic and comfortable with the camera, Tan is the subject of a feature documentary by filmmaker Evans Chan, Sorceress of the New Piano: The Artistry of Margaret Leng Tan,which receives its New York premiere at the Pioneer Two Boots Theater on September 23/24.

Related:

Categories: spotlight

Tags: CAGE NAM JUNE

CAGE NAM JUNE: Panel In New York

Panel Discussion in Paris, Moderated by George Quasha

Saturday, October 28th 2006, 6pm

Accompanying the exhibition, CAGE NAM JUNE: A Multimedia Friendship, ZONE: Chelsea Center for the Arts presents:

Panel Discussion in Paris during Digital Video Art Fair

Moderated by George Quasha

Panelists:

artist Jackie Matisse

author Charles Stein

artist Gary Hill

artist Molly Davies

artist Tom Johnson

Saturday, October 28th 2006

6pm

at Theatre La Reine Blanche

2 bis passage Ruelle, 75019 Paris, France

Molly Davies

Molly Davies started making experimental films in the late 1960s in New York City. For multi media performance pieces she has collaborated with artists including John Cage, David Tudor, Takehisa Kosugi, Lou Harrison, Michael Nyman, Alvin Curran, Fred Frith, Suzushi Hanayagi, Sage Cowles, Polly Motley, Jackie Matisse and Anne Carson. Her work has been presented at such sites as the Venice Film Festival, the Centre Pompidou, Musee de l’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Musee Art Contemporain Lyon, The Getty, Theatre Am Turm, the Whitney Museum, the Walter Arts Center, the Kitchen, La Mama Etc., Dance Theatre Workshop, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival and the Indonesian Dance Festival. Her work is in the collections of the Getty Research Institute, the Musee Art Contemporain Lyon and the Walker Art Center. She teaches courses in design for inter-media performances at universities in the United States, Europe and Asia.

Gary Hill

Gary Hill is one of the most important contemporary artists investigating the relationships between words and electronic images — an inquiry that has dominated the video art of the past decade. Originally trained as a sculptor, Hill began working in video in 1973 and has produced a major body of single-channel videotapes and video installations that includes some of the most significant works in the field of video art. His first tapes explored formal properties of the emerging medium, particularly through integral conjunctions of electronic visual and audio elements.

His installations and tapes have been seen throughout the world, in group exhibitions at The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; Documenta 8, Kassel, West Germany; Long Beach Museum of Art, California; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, and the Video Sculpture Retrospective 1963-1989, Cologne, West Germany, among other festivals and institutions. Hill’s work has also been the subject of retrospectives and one-person shows at The American Center, Paris; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; 2nd International Video Week, St. Gervais, Geneva; Musee d’Art Moderne, Villeneuve d’Ascq, France; and The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Gary Hill created new large scale works for his solo exhibition at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris, October 27, 2006 – February 4, 2007.

Jackie Matisse

Born in France, Jackie Matisse lived in New York until 1954. Since then she has lived in Paris making frequent visits to New York. Between 1959 and 1968 she worked for Marcel Duchamp, completing the assemblage of the “Boite en Valise”. At this time using her married name, Jacqueline Monnier, she began to make kites “in order to play with color and line in the sky”. In 1980 she showed kites which were created to be used underwater at the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York, and since then has continued to make kitelike objects intended for three different kinds of space: the sky, the sea, and indoor space, all linked through her use of movement.

George Quasha

Artist and poet George Quasha works across mediums to explore principles in common within language, sculpture, drawing, video, sound, installation, and performance. His axial stones and axialdrawingshave been exhibited in New York’s Chelsea at Baumgartner Gallery and ZONE Chelsea Center for the Arts, and elsewhere, and are featured in the newly published book, Axial Stones: An Art of Precarious Balance(Foreword by Carter Ratcliff) (North Atlantic Books: Berkeley).

For his video installation art is: Speaking Portraits (in the performative indicative),he has filmed some 500 artists, poets, and composers (in 7 countries and 17 languages) saying “what art is.” His video works (including Pulp Friction, Axial Objects, Verbal Objects) have appeared internationally in museums, galleries, schools, and biennials. A 25 year performance collaboration (video/language/sound) continues with Gary Hill and Charles Stein.

In 2006 he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in video art.

His other 14 books include poetry (Somapoetics, Giving the Lily Back Her Hands,Ainu Dreams [with Chie Hasegawa],Preverbs); anthologies (America a Prophecy [with Jerome Rothenberg], Open Poetry[with Ronald Gross],An Active Anthology[with Susan Quasha], TheStation Hill Blanchot Reader); and writing on art (Gary Hill: Language Willing;with Charles Stein: Tall Ships, HanD HearD/liminal objects,Viewer).

Awards include a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in poetry. He has taught at Stony Brook University (SUNY), Bard College, the New School, and Naropa University. With Susan Quasha he is founder/publisher of Barrytown/Station Hill Press in Barrytown, New York.

Charles Stein

Charles Stein is the author of Persephone Unveiled (a study of the Eleusinian Mysteries), eleven books of poetry including The Hat Rack Treeand the forthcoming From Mimir’s Headfrom Station Hill /Barrytown, Ltd., a long-term poetic project, theforestforthetrees, translations of Greek epic, philosophical, and Hermetic poetry; a critical study of the poet Charles Olson and his use of the writings of C.G. Jung called The Black Chrysanthemum(also from Station Hill Press). His work has been anthologized in such collections as Poems for the Millennium (U. of California Press), Hazy Moon Enlightenment(Shambala),Technicians of the Sacred(U. of California Press),Text-Sound Texts(Morrow), Open Poetry(Simon and Schuster) and has appeared in such magazines as American Poetry Review, Alcheringa, Caterpillar, Conjunctions, Ear Magazine, Perspectives of New Music, Temblor, Sulphur, Open Space,and many other poetry journals. He was the editor of an anthology Being=Space X Action: Searches for Freedom of Mind in Art, Mathematics and Mysticism.

He received an Individual Writer’s Grant from the National endowment for the Arts for 1978-79, and was the winner of the Wallace Stevens Poetry Prize in 1973.

He plays Gregory Bateson in video-installation artist Gary Hill’sWhy Do Things Get in a Muddle?and is one of the two performers (with George Quasha) in Gary Hill’s Tale Enclosure. He collaborated with Gary Hill and Paulina Wallenberg-Olsson in the creation of Dark Resonances—a performance/installation at the Colosseum in Rome. For three decades he has worked with George Quasha in the production of “dialogical” critical texts, including three books: Hand Heard/liminal objects: Gary Hill’s Projective Installations—Number 1, Tall Ships: Gary Hill’s Projective Installations—Number 2,and Viewer: Gary Hill’s Projective Installations—Number 3.His other collaborative writing with George Quasha related to Gary Hill’s work has appeared in art catalogues of the Stedelijk Museum of Amsterdam, the Kunsthalle of Vienna, the Barbara Gladstone Gallery of New York, Public Access of Toronto, the Voyager Laserdisc Gary Hill, etc.

In collaboration with Gary Hill and George Quasha, he has performed at the Long Beach Museum of Art, California, The Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, England, The Rhinebeck Performing Arts Center.

As a multi-media artist and “Sound Poet” his graphic “Text-Sound Texts” have been anthologized and performed by himself and others; his drawings have appeared as accompaniments to his own poetry. He has performed his sound poetry at the International Sound Poetry Festival, The New Moon Festival, The New Image Theater, as well as at numerous University sponsored, music, and literary venues.

His photography has appeared in exhibitions at The College Art Gallery of SUNY New Paltz, The University of Connecticut Library in Storrs, The Arnolfini Arts Center in Rhinebeck, New York, the Robert Louis Stevenson School in New York, New York, and on the covers of numerous books of poetry and fiction.

He holds a Ph.D. in literature and has taught at SUNY Albany, Bard College’s Music Program Zero, and The Naropa Institute.

He currently resides in Barrytown, New York.

Related

Categories: spotlight

Tags: CAGE NAM JUNE

CAGE NAM JUNE: A Multimedia Friendship Panel Discussion

Panel Discussion, Moderated by Kenneth Silverman

Thursday, October 19th 2006, 7pm

Panel Discussion, Moderated by Kenneth Silverman

Thursday, October 19th 2006, 7pm

Panel Discussion, Moderated by Kenneth Silverman

Thursday, October 19th 2006, 7pm

Panel Discussion, Moderated by Kenneth Silverman

Thursday, October 19th 2006, 7pm

Accompanying the exhibition, CAGE NAM JUNE: A Multimedia Friendship, ZONE: Chelsea Center for the Arts presents a Panel Discussion with four people who knew and worked with Cage and Paik.

Panelists:

the Fluxus artist Alison Knowles

vocalist/composer Joan La Barbara

dancer and dance historian David Vaughan

writer and critic William S. Wilson

curator Kenneth Silverman

Thursday, October 19th, 2006

6:30pm

ALISON KNOWLES was born in New York City. She works in the field of visual art, making performances, sound works and radio shows (Hoerspiele). She attended Scarsdale High School, Middlebury College and graduated with an honors degree in Fine Art from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. She married the Fluxus artist Dick Higgins and worked for the Something Else Press doing special editions by silkscreen, engaged in events with the Fluxus group and birthed twin daughters Hannah B and Jessica in 1964. Her installation The Big Book was made in New York, and toured in Canada and Europe, collapsing in California in the mid-seventies. For three years she was Associate Professor of Art at California Institute of the Arts in the department of Alan Kaprow. Her computer instigated dwelling The House Of Dust is located in California as a permanent installation. During the late seventies and eighties she extended her studio to include a shop in Barrytown, New York, a stone’s throw from the Hudson River. During the eighties she has worked in Italy and Germany and Japan doing multiples, unique pieces and radio plays. Her second walk-in book The Book Of Bean from 1983 appeared in Venice. Her most recent exhibitions include “Um-Laut” in Koln and “Indigo Island” in Warsaw. She maintains a studio at 122 Spring St. in New York.

DAVID VAUGHAN was born in London and educated at Oxford University. He studied ballet with Marie Rambert and Audrey de Vos. In 1950 he continued his studies at the School of American Ballet, later studying with Antony Tudor, Richard Thomas, and Merce Cunningham. He has worked as a dancer, actor, singer, and choreographer, on film and television, in ballet and modern dance companies, and in cabaret. He is associate editor of Ballet Review and the Encyclopaedia of Dance and Ballet. He is the author of Frederick Ashton and His Ballets and the forthcoming Merce Cunningham: 50 Years, for which he received a Guggenheim Fellowship; and he has contributed to Dancers on a Plane: Cage, Cunningham, Johns and to Ornella Volta’s Satie et Ia danse. He has been associated with Merce Cunningham Dance Company since 1959, as archivist since 1976. He has taught dance history and criticism at New York University, the State University of New York/College at Purchase, the Laban Centre for Movement and Dance, the University of Chicago Dance History Seminar, and the American Dance Festival Critics’ Conference. In 1986 he was Regents’ Lecturer at the University of California.

JOAN LA BARBARA was born in Philadelphia, PA. Educated at Syracuse and New York Universities and Tanglewood/Berkshire Music Center, studying voice with Helen Boatwright, Phyllis Curtin and Marian Szekely-Freschl, she learned her compositional tools as an apprentice with the numerous composers with whom she has worked for three decades. Her career as a composer/performer/soundartist explores the human voice as a multi-faceted instrument expanding traditional boundaries, creating works for multiple voices, chamber ensembles, music theater, orchestra and interactive technology, developing a unique vocabulary of experimental and extended vocal techniques: multiphonics, circular singing, ululation and glottal clicks that have become her “signature sounds”, garnering awards in the U.S. and Europe. La Barbara has collaborated with artists including Lita Albuquerque, Cathey Billian, Melody Sumner Carnahan, Judy Chicago, Ed Emshwiller, Kenneth Goldsmith, Peter Gordon, Bruce Nauman, Steina, Woody Vasulka and Lawrence Weiner. In the early part of her career, she performed and recorded with Steve Reich, Philip Glass and jazz artists Jim Hall, Hubert Laws, Enrico Rava and arranger Don Sebesky, developing her own unique vocal/instrumental sound. In addition to the internationally-acclaimed “Three Voices for Joan La Barbara by Morton Feldman” “Joan La Barbara Singing through John Cage” and “Joan La Barbara/Sound Paintings”, she has recorded for A&M Horizon, Centaur, Deutsche Grammophon, Elektra-Nonesuch, Mode, Music & Arts, MusicMasters, Musical Heritage, Newport Classic, New World, Sony, Virgin, Voyager and Wergo. Recording projects as singer and/or producer include “Only: Works for Voice and Instruments” by Morton Feldman”; “Rothko Chapel/Why Patterns”, “John Cage at Summerstage with Joan La Barbara, Leonard Stein and William Winant”, Cage’s final concert performance on July 23, 1992 in NYC’s Central Park. La Barbara was Artistic Director of the Carnegie Hall series, “When Morty met John”, celebrating the music of John Cage and Morton Feldman and The New York School; is Artistic Director, Curator and Host of “Insights”, a new series of encounters with distinguished composers, for The American Music Center; and co-produces the “EMF 10” concert series in New York City. Joan La Barbara is a member of SAG, AFTRA, AEA, The American Music Center, and is a composer and publisher member of ASCAP.

WILLIAM S. WILSON, who was graduated with a Ph.D. from Yale University, has taught the writing of fiction at Queens College and the Graduate Writing Division of Columbia University. Author of a book of short stories, Why I don’t write like Franz Kafka, he has been writing essays about visual art since 1964. Nam June Paik lived in a studio in his house during1964-65. He has given talks about Eva Hesse in Paris, London, San Francisco and New York.

Kenneth Silverman – Curator Kenneth Silverman is Professor Emeritus of English at New York University. His books include Timothy Dwight; A Cultural History of the American Revolution; The Life and Times of Cotton Mathe; Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance; HOUDINI!!!.; and Lightning Man: The Accursed Life of Samuel F. B. Morse. A fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, he has received the Bancroft Prize in American History, the Pulitzer Prize for Biography, the Edgar Award of the Mystery Writers of America, and the Christopher Literary Award of the Society of American Magicians. Currently he is writing a biography of John Cage.

Related

Categories: spotlight

Tags: CAGE NAM JUNE

The Villager interviews Molly Davies

"Redefining the ordinary", January 18 -24, 2006, Vol. 75 No. 35

Villager photo by Jefferson Siegel

Film and video artist Molly Davies

The Villager

Redefining the ordinary

By Nicole Davis

At first glance, the group of crates, piled haphazardly in a corner of this Chelsea gallery, looks nothing like the rest of the work on view at Molly Davies’ first New York retrospective of her forty-year career. She is, after all, a film and video artist, so stumbling upon these Chinese produce crates, which house illuminated scenes from parks in Paris and Berlin, and emit, from some speaker somewhere, a chorus of tree frogs, seems like a curatorial mistake. In fact, the installation, titled “Dislocation,” may be the most symbolic of Davies’s signature style — changing the meaning of the most ordinary things through some savvy repackaging.

Five video installations over three decades show the many sides of this meditative video artist, who says she often films first, and decides on the structure later. One of the least visually arresting works in the show, “David Tudor’s Ocean,” has perhaps the best back-story. Its inspiration sprang from a conversation with Nam Jun Paik, commonly called the godfather of video art. He told Davies she should make a documentary of David Tudor, a friend and avant garde musician for whom John Cage created piano and electronic compositions.

“But I don’t do documentaries,” Davies explained.

“Just shoot his hands,” Paik told her.

So she did. She filmed hours and hours of footage of Tudor setting up and creating the music for a Merce Cunningham dance performance that Tudor, then the company’s music director, scored with a half-finished composition by Cage called “Ocean.”

“I shot it in 1984 — and as always, it took three years for me to figure out what to do with it,” says Davies. She ultimately decided to split the footage between the slow, methodical act of preparation and the seamless, seemingly effortless process of performance. Three of the six screens in the installation show Tudor setting up for the 90-minute show — one for each day of set up. Every so often one of these screens flashes, which signals where the film was cut. On the other three screens — one for each day of the performance — there are no edits, and hence no flashes, only a continuous loop of Tudor as he plays (or programs) the electronic music from the pit while the dancers move on stage.

“It’s a portrait of the working process through detail and accumulation,” says Davies, a statement that applies just as well to her collected body of video art. In “Sea Tails,” for instance, we see her collaborative style at work. “I almost always work with friends and family,” says Davies, who fortunately knows some very talented people. Filmed over a week in the Bahamas, it brings together the underwater kites created by friend and artist Jackie Matisse and the music of David Tudor, who stayed on board and recorded the marine sounds while Davies filmed the billowy, colorful movement underwater. There is a method at work in the finished product: At all times, a pair of screens — there are three pairs, or six screens, altogether — displays the kite’s movement in unison as three different speakers play a different Tudor composition simultaneously. That may be much to grasp on paper, but in person it gels beautifully as the kites flow like seaweed to the sound of the snaps and cracks beneath the aquamarine water.

This multi-layered approach is echoed in “Dressing,” where we see her partner of 16 years, dancer Polly Motley, performing the simple act we repeat each morning, on three different screens. “It’s basically just putting appendages through holes,” says Davies, but through her multi-monitor-lens, as we watch Motley slowly button her shirt and zip her slacks, this quotidian chore becomes sensual, even erotic.

Davies, who has lived in her loft at Broadway and Great Jones for the past 20 years, began making films in the late 60s to document her friends and family.

“I was hanging out with the great documentary makers” — the ones responsible for bringing cinéma vérité to the New World — “DA Pennebaker and Richard Leacock, and I was so struck by their ability to get those everyday moments.” She continued making films and teaching when she moved to St. Paul with then-husband, conductor Dennis Russell Davies. There, she met dancer Sage Cowles, and began what would become a ten-year collaboration on performance pieces that featured multiple screen projections of Cowles while she performed on stage. (Last spring, for Cowles’s 80th birthday, they reconstructed their seven-piece oeuvre at Dance Theater Workshop and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.) Davies says she ultimately embraced video installations because it freed her from the constraints of live performance. “I wanted the time to construct something in the way I wanted to construct it,” she says.

When Davies returned to New York in 1984, she also took time to raise her life’s other important work: her children, three from her marriage, along with two of Polly’s. It is one reason she did not stay in the forefront of video art like a contemporary of hers, Bill Viola, who is actually a few years her junior. “It’s a crucial time — between 40 and 50, if you’re not out there in New York, you kind of drift off the map. I’m probably better known with the dancers,” says Davies, who, despite her 62 years and two grandkids, sports a spiky haircut and stylish threads that make her one very hip grandmother, with plenty of fire left.

It shows in the other work on view, like “Desire,” in which a playful conversation among friends takes on sexual undertones, and in “Pastime,” a multi-layered work that turns a simple summer afternoon of play with mother and son into something downright Oedipal.

“I shot it because of the absolutely riveting beauty of the afternoon light,” she said, unaware of how provocative the scene was at first. But somewhere deep down she picks up on these intimate undercurrents that run through the most innocent of scenes.

“You don’t always see the significance of these moments initially. But then you go home, and go into the studio, and it reveals itself to you.”

Related:

Categories: news

Tags: Molly Davies