Demons • The Light

Installation view

Demons • The Light

Installation view

Demons • The Light

Installation view

Demons • The Light

Installation view

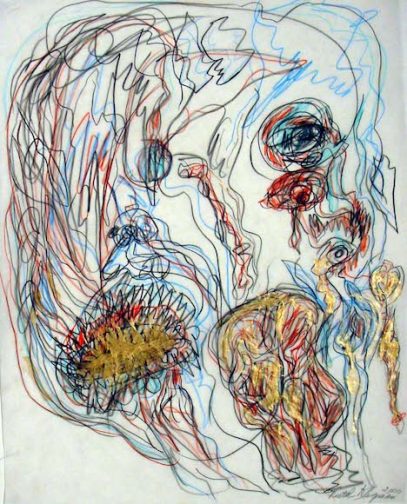

Demon: Beginning, 2000

Color pencil and metallic acrylic on onion skin paper

18 x 24 in.

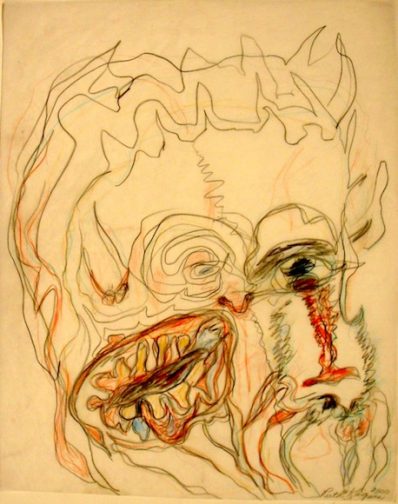

Demon I, 2000

Color pencil and metallic acrylic on onion skin paper

18 x 24 in.

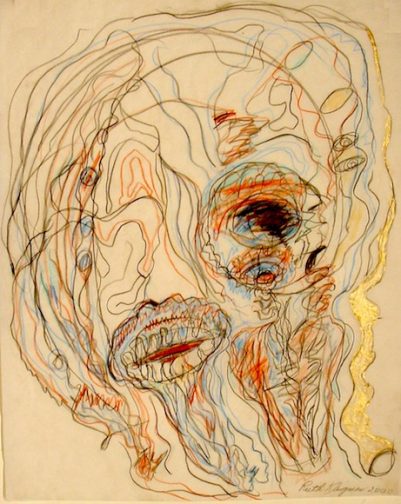

Demon Disintegration I, 2000

Color pencil and metallic acrylic on onion skin paper

18 x 24 in.

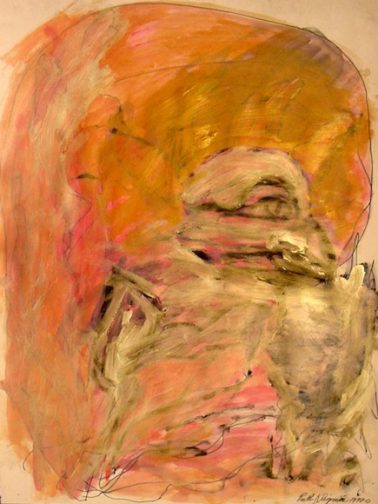

Demon: Horus I, 2000

Metallic acrylic on paper

18 x 24 in.

Demon: Horus II, 2000

Metallic acrylic on paper

18 x 24 in.

Landscape of the sky: September, 2002

Acrylic on canvas

72 x 72 in.

Landscape of the sky: June, 2002

Acrylic on canvas

72 x 72 in.

Landscape of the sky: August, 2001

Acrylic on canvas

72 x 72 in.

ZONE:Chelsea Center for the Arts is proud to announce DEMONS•THE LIGHT, new work by Ruth Kligman. Recently, Kligman’s paintings have gazed back to the quiet of a time before she was born—the moment when one of the seeds of American painting’s triumph began to germinate in a cultivated garden in France: Monet’s explorations of vision itself, his dissection of shape, figure, ground, and color. His monumental Water Lilieslaid a solid foundation for modern painting by atomizing nature and making the plane on which paint was brushed, layered, scumbled, and dragged into an experience that fast lost any narrative quality, becoming one of the sensations defining the modern world. The interlocking palimpsests of experience that Monet conjured from the water are reflected in the flecks of color and shifting shades that make up the ethereal atmosphere of Kligman’s landscapes of the sky.

But Kligman’s spiritual icons of the 1980’s and her more recent explorations of enveloping light have alternated with those demons that first loomed up in the 1960’s, drawn on onion skin with colored pencils and metallic pigments. The end of the millennium saw a resurgence of figurative expressionism across the art world; Kligman’s came from a place of re-examined tragedy. Like so many of her peers during the anxious 1950’s (which, as today, found New York City pegged on the bull’s-eye of a war between ideologies), Kligman had been in psychoanalysis—her Monster series seems to have sprung from an unconscious that was never fully allowed to rest. Monster: Horus and Monster: Disintegration are direct channels back to the automatic drawing and primal Jungian imagery that freed up the New York School generation; Kligman’s works carry on this tradition but take it to a place of her own making. In Demons, similar compositions begin with rounded, swirling layers shot through with jagged forms, then transmute into recognizably demonic visages before melting into squalls of orange, blue, and black. Kligman uses long, unbroken color-pencil outlines to define these strange entities and then energizes the overlapping skeins with metallic flashes of paint. The Horus series engages the viewer through broad areas of color that alternately suppress or yield to the writhing black, skeletal frameworks underneath; these are works of tense beauty.

The American century of art has had its share of glories and demons, and throughout, Ruth Kligman has been its abiding witness.

Ruth Kligman

DEMONS • THE LIGHT

January 20 – March 25, 2005

Opening Reception

6-8PM, Thursday January 20, 2005

A room of minimalist water lilies in lip gloss muted colors, industrial cosmetics contemporary feel, very spare, hardly there, muted colors, slight sheen, five foot square canvases end to end and on, a quiet contemplation, ephemeral, lurking. They are not water lilies. They are light. Abstract markings. Nudges. The least mark applied with extreme presencing by a master in command of her medium and taking the space for an entirely cosmic ride. One hears chords in the distance not quite dissonant and haunting. The experience in the room grows with time. The Rothko chapel in Houston has such an effect of the powerful ethereal.

But then the drawings are just the opposite. Dragons. Demonic scribbles that grows even more dynamic through her abstracting of these emerging tail cracking fire breathing enchanting monsters. Well they are in another room in the gallery, just as we keep our shadow side on the right side of the neo cortex of the brain. But these demon drawings are compelling, aggressive, raging marking, expressionist. Antonin Artaud drew a comparable series of automatist ravings shown at the Met a few years back. THEN WE RETURN TO THE HUGE MINIMAL CONTEMPLATIONS AND THE MINIMAL MARKING HAS JUST A HINT OF A DRAGONS TAIL FLICKERING THROUGH THE MIST. AHA. The hidden tension in these very spare works is now palpable. I am reminded of Barnet Newman crosses buried under the very minimal paint.

Ruth Kligman is at the top of her game as a painter. An artist with a fabulous history that is just surfacing into rewriting, as feminist theory evolves to dispel the onus on the mistress, making her a person and a painter in her own right. It is the right time to place Ruth Kligman properly in art history. She is no longer the art student among art giants, the beauty seen as the muse who launched a thousand abstract expressionist paintings, and psychotherapists now grasp that the new girl didn’t wreck the marriage in the first place it was more complex than that. Indeed one has to marvel that both Pollock and deKooning found her so conversational for years on end. What did they see? It is astonishing that men are never implicated in bedtime stories only women, ever. What mistress or kept man has had this reflected on his status as an artist I can’t think of one. Camille Claude only emerged as the sculptor rival of Rodin out of the shadow of master? A hundred years later? It is an epic we speak of, that the culture is now looking. Looking at art. Seeing context and history but really looking. Without dismissing offhand the work of women. Did this happen? Consult Gorilla Girls statistics for the gory facts.

Ruth Kligman is one of the towers of abstract expressionism and when this is outed many historians and critics will suddenly come forward with oh I always suspected, after years of hesitation to break from the dark hand. I like very much that she is painting from her self. Rapturous. Engaged. Moody and blooded and moaning and singing with the gods. Postmodernism has no idea how to approach this phenomenon. A lucky fool. A painter invoking the cosmic rain come donor, there was another painter who danced the cosmic rain come down. Jackson Pollock. When I asked Clem Greenberg what he felt about the spiritual in Pollock work, he stopped and snorted ineffable, – we don’t discuss that. Now we can discuss that.

Barnaby Ruhe, PhD, Senior Editor, Art/World, professor of art NYU, Artist/lecturer MoMA

The arc of Ruth Kligman’s life is reflected in the half-century evolution of her art, which spans the moment Irving Sandler christened “The Triumph of American Painting” and the myriad styles that coexist today. Mentored by Willem de Kooning in the late 1950s, Kligman’s early large-scale compositions are a strong opening act from a woman painting in the macho arena of abstract expressionism, conveying both the movement’s brio and its poignancy. The ambitious swagger of the era can be felt in the slashing reds and blacks that speed across an eight-foot canvas titled The Bullring; its emotions suffuse Broken Cosmos, where sullied whites and bruised magentas entwine sandy ochres, echoing the doubt and struggle of the generation of artists who broke the ice and brought forth an American art that finally elevated the New World to the firmament of the Old.

Rather than looking toward the figures underpinning much of de Kooning’s work, Kligman’s bold abstractions moved into the wide-open spaces of color-field painting. Throughout the 1960s her work retained its broad scale while the contrast between colors deepened, until finally they were stripped down to emphatic black and white contours pushing against the classic rectangular format. The Two of the Both of Us plays with curves jammed into right-angled corners or pressed against the straight edges of the canvas, like two lovers confined to a narrow, rigid bed. Following these, Kligman began to shape her canvases into totems of color, as in Coney Island Baby, where an orange oval (an egg?) provides the weight that balances a thrusting nine-foot chevron of blue.

There is a hint of darkness underlying this period, something welling up from underneath. In Birth (Early Monster), a 7’ x 8’ oil, an organic shape, like the lithe cross-section of a pelvis, has been brushed onto the canvas, heavy black outlines constraining muted, variegated grays. The compressed shapes railing against the edges of her canvases were holding something at bay.

Kligman, of course, had an affair with Jackson Pollock and was with him the night he died. It was Pollock, as de Kooning stressed, who “broke the ice” for all the painters who came after by breaking contact with the canvas—by pouring and dripping paint in exquisite arabesques of color that delicately traced the movements of his body. Kligman recalled, as own her work began to mature a few years later, “The expression became alive . . . a frenzy yet deliberate . . . the abyss of the unknown, jumping off the edge . . . Abstract Expressionism . . . when it worked it was an epiphany.”

The luminosity of fluid silver radiator paint—given a rosy flush through its mingling with a passionate skein of red that unveils a black figure—floods the painting Pollock made for Kligman. That hopeful glow colored her youth, and it reverberates in the luminous metallic paintings and works on paper she created in later decades. In the 1980s and ’90s, Kligman’s faith in art inspired reflective (both figuratively and literally) compositions incorporating the image of the cross, harking back to Byzantine icons whose precious metals foreshadowed the awaiting heavenly paradise. Monolith, Silver Cross, and Turquoise Cross bring out subtleties at the most basic intersection of light and surface.

Recently, Kligman’s paintings have gazed back to the quiet of a time before she was born—the moment when one of the seeds of American painting’s triumph began to germinate in a cultivated garden in France: Monet’s explorations of vision itself, his dissection of shape, figure, ground, and color. His monumental Water Lilieslaid a solid foundation for modern painting by atomizing nature and making the plane on which paint was brushed, layered, scumbled, and dragged into an experience that fast lost any narrative quality, becoming one of the sensations defining the modern world. The interlocking palimpsests of experience that Monet conjured from the water are reflected in the flecks of color and shifting shades that make up the ethereal atmosphere of Kligman’s landscapes of the sky.

But Kligman’s spiritual icons of the 1980’s and her more recent explorations of enveloping light have alternated with those demons that first loomed up in the 1960’s, drawn on onion skin with colored pencils and metallic pigments. The end of the millennium saw a resurgence of figurative expressionism across the art world; Kligman’s came from a place of re-examined tragedy. Like so many of her peers during the anxious 1950’s (which, as today, found New York City pegged on the bull’s-eye of a war between ideologies), Kligman had been in psychoanalysis—her Monster series seems to have sprung from an unconscious that was never fully allowed to rest. Monster: Horus and Monster: Disintegration are direct channels back to the automatic drawing and primal Jungian imagery that freed up the New York School generation; Kligman’s works carry on this tradition but take it to a place of her own making. In Demons, for example, similar compositions begin with rounded, swirling layers shot through with jagged forms, then transmute into recognizably demonic visages before melting into squalls of orange, blue, and black. Kligman uses long, unbroken color-pencil outlines to define these strange entities and then energizes the overlapping skeins with metallic flashes of paint. The Horus series engages the viewer through broad areas of color that alternately suppress or yield to the writhing black, skeletal frameworks underneath; these are works of tense beauty.

The American century of art has had its share of glories and demons, and throughout, Ruth Kligman has been its abiding witness.

R.C. Baker has exhibited his artwork at the Drawing Center, the Center for Book Arts, White Columns, and other venues in and around New York City; his writing has appeared in The New York Times, the Village Voice, the Performing Arts Journal, and other publications.

Ruth Kligman’s new work DEMONS and THE LIGHT is being shown at the ZONE 601 W 26thSt. Suite 302. Kligman’s art has a quiet power. Her art is not demanding attention, nor is there an attempt to convince a viewer of its worth. Her off-handed approach to art making, allows for an innocent and unpredictable range of expression. A tangled mass of colored pencil lines on onion-skin-paper has a completely unexpected material presence that is defined by the artist’s hand. In a careful balance of physical marking and emerging imagery, the presence of a ‘demon’ as a bundle of co-existing perspectives, defines itself in a viewer’s imagination. Images of demons become objects of sheer beauty. The ‘Demon’ drawings define a format for automatic image creation that allows for the freedom of expression that is essential to the uncensored emotive impact that emerges from each piece. This art lives in the ‘zone’ where the abstract expressionists left the illustrative shackles of Surrealism and defines the ‘surrealist expression’ as a state of mind to be experienced directly.

The Light begins with a group of small paintings on paper that Kligman calls the Cosmic Series. In these heavily painted surfaces, brush strokes are played down and give way to a massing of metallic paint that seems to smooth and polish a surface. But what is it? It does not depict anything. It reflects light casually. It seems like an unfamiliar piece of material. It is an object that glows. It holds light, shines; it maintains its strangeness. It refuses to give in to easy definition. This is not Neo Geo or a return to minimalism. It is a vision of painting construction that maximizes intuitive freedom within defined boundaries. The art making is held in check and freed simultaneously.

A third group of paintings in this show is influenced by the Cosmic Series. This time the painting is on canvas and large scale. Six ft. square canvases are butted against one another to form architectural installations. One wall has three canvases on it. The adjacent wall has five. The surfaces are built by scumbled, slashed and layered off-whites and subtle metallic paints that change color, like an oil slick, as the viewer walks by them. In the paper pieces, the strokes are barely distinguishable from their job of shining the paper surface. In the canvases, the brushwork is purposefully exposed, thereby creating a landscape arrangement to the marking. The painterly application of the paint in this series (Landscapes Of The Sky) is more familiar as painting, making the paper works ever stranger.

David Hatchett

RUTH KLIGMAN

EDUCATION:

Studied painting and Art History at the New School for Social Research, New York University and Yale. Studied with Larry Rivers, Gregorio Prestopino, Abraham Rattner, Reginald Marsh and Willem De Kooning.

SELECTED EXHIBITIONS:

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2005 “DEMONS • THE LIGHT”, ZONE: Chelsea Center for the Arts, New York

1988 New York Studio Show, sponsored by Sur Rodney Sur

1987 Otis Gallery, London, England

1986 M. Donahue Gallery, New York, New York

1984 “Pier Show”, Brooklyn, New York

1983 Pier 34, New York, New York

P.S 1, New York, New York

1966 Ivan Spence Gallery, Ibiza, Spain

1964 Gallery International, New York, New York

1962 Thibaut Gallery, New York, New York

1959 March Gallery, New York, New York

Tangier Gallery, New York, New York

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

1989-90 Spencer Throckmorton Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico

1987 Wessel O’Connor Gallery, Rome, Italy

Christies Gallery, London, England

369 Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland

Richard DeMarco Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland

1986 Minneapolis Museum of Art, Minneapolis, Minnesota

1985 Kamikazi Gallery, New York, New York

Neo Persona Gallery, New York, New York

1984 Shuttle Gallery, New York, New York

1967 Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York

1958 Martha Jackson Gallery, New York, New York

Categories: exhibitions

Tags: Ruth Kligman