River Rocks and Smoke 4/11/90, 1990

Water color on paper prepared with smoke

28 x 42 in. (70 x 101 cm)

New River Watercolor, SeriesIV, 1988

Watercolor on paper

26 x 40 in.

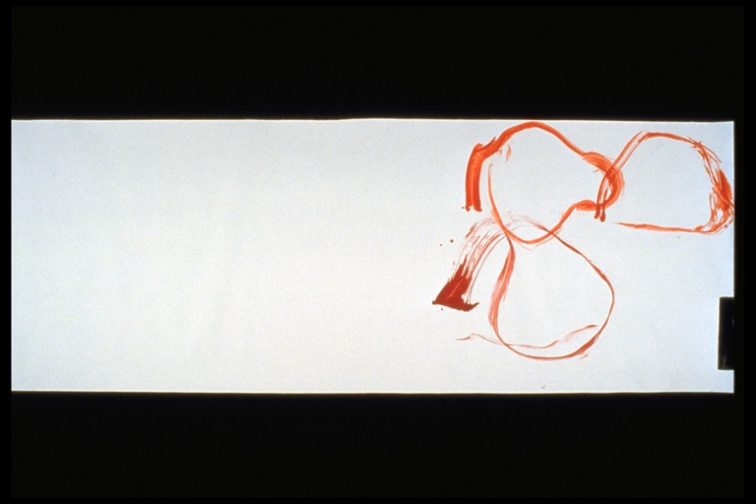

New River Watercolor, SeriesII, 1988

Watercolor on paper

26 x 40 in.

River Rocks and Smoke, 4/11/90, 1990

Water color on paper prepared with smoke

27 x 40 in.

River Rocks and Smoke, 4/12/90, 1990

Water color on paper prepared with smoke

27 x 40 in.

ZONE: Chelsea Center for the Arts, presents its second exhibition in 2004 of visual art works by the late avant-garde composer, writer, artist and philosopher John Cage (1912-1992).

John Cage: Watercolors, Selected Drawings and Prints,* articulates the relationship of Cage’s watercolor paintings to his important involvement with printmaking, during which his fourteen year-long (1978 – 1992) experience at Crown Point Press transformed the traditional discipline of etching as surely as he had reinvented our idea of music thirty years earlier. His late-career watercolor paintings were created at the Mountain Lake Workshop in the rural Appalachian Mountains of Virginia between 1983 and 1990. They demonstrate, like his graphic works, a profound sense of beauty not usually associated with Cage’s dismissal of conventional aesthetics.

The watercolors shown here reveal the dynamic interaction with his graphic art works (mostly unique images), including the Ryoanji drawings that occupied his attention for eleven years. This exhibition offers an essential visual component to complement Cage’s lifelong achievement as America’s foremost avant-garde composer and artist, and highlights his role as the principal mediator of the influence of Asian culture and philosophy on his generation and those to follow. Cage’s visual art, like his writing, brings an even wider audience to his uniquely pioneering work and contributes to a broader understanding of his strategic use of “chance operations” in his music, writing, printmaking and painting as a way to redirect our pre-conceived and authoritarian attitudes toward the arts.

* Guest-curated by Ray Kass, founder and director of the Mountain Lake Workshop, in which John Cage produced his watercolor paintings between 1983 and 1990

JOHN CAGE: Watercolors, Selected Drawings and Prints

November 18 – December 18, 2004

Opening Reception

6-8PM, Thursday November 18, 2004

John Cage: Watercolors, Selected Drawings and Prints

Ray Kass, Guest Curator

Ray Kass is an artist and the founder and director of the Mountain Lake Workshop of the Virginia Tech Foundation, where John Cage produced his watercolor paintings between 1983 and 1990. He is Professor Emeritus of Art at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in Blacksburg, Virgina.

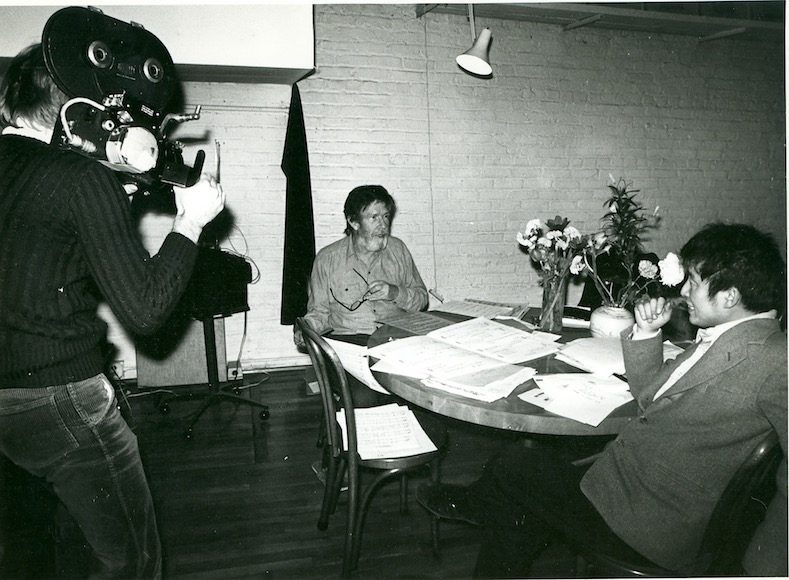

I became aware of John Cage’s visual artwork and printmaking activities at Crown Point Press when I had the opportunity to interview him in 1980.1

During the course of our visit, Cage showed me an example of the work he was involved with at Crown Point, an etching entitled “On The Surface” (1980 – 1982), and some of the materials employed in the process (cut up copper etching plates). Cage described how he had used “chance operations” with the aid of a computer program derived from the method of random access of the ancient Chinese book of wisdom, the I–Ching, in making the complex print. He also described an even more complicated procedure for another related etching, also still in progress, entitled “Changes and Disappearances” (1979-82), and that used “chance” to incorporate an even more various array of imagery.2It occurred to me that his etchings had an extraordinary correspondence to the methods he utilized in composing his music – and that they were visual counterparts of sorts, related in a manner that one might not have expected (i.e. Schoenberg’s watercolors, for instance, don’t seem directly related to his composing anymore than Victor Hugo’s ink drawings and gouaches appear directly related to his novels). But the connection between Cage’s use of “chance” methodology in his various kinds of work (composing, writing, installation & performance art, & now printmaking) made sense in a way that awakened me to the great scope of his work.

In subsequent visits with Cage over the next three years he continued to show me examples of the etchings that he was working on at Crown Point, including a series entitled Where R = Ryoanji (1983), and a new group of related drawings. The Ryoanji etchings consist of patterns of circular overlapping lines incised with a sharp dry point etching tool around stones placed by Cage’s chance operations on a copper plate. The Ryoanji drawings utilized the same stones, but they are drawn around with pencils and are basically simpler in execution than the prints; Cage worked on them at home intermittently for the rest of his life. He commented to his friend and agent, Margaret Roeder, that he considered the Ryoanji drawings as “ a form of meditation”.3

Before I saw the Ryoanji drawings, I had never sensed a vital relationship between the tradition of drawing and that of painting and any of Cage’s earlier graphic arts; in contrast, those works seemed insistently unconventional in their demonstration of randomly acquired effects. Despite the fact that Cage had rendered the Ryoanji drawings in an unselfconscious, almost automatic way intended to avoid any “personal” stylistic manner, these works exhibit an implicit quality of hand gesture, however randomly acquired, and associated with the formal conventions of drawing. I asked Cage whether, since his early experiences with painting in the late ‘20s and early ‘30s, he had ever again thought seriously about painting; he said he had really not had time to consider it.

*

In spring 1983 I invited John Cage to direct a mycological foray (mushroom hunt) at Mountain Lake and to give a gallery talk at the opening of an exhibition of his prints and drawings that I had organized at nearby Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. During the several days of the 1983 workshop there were periods of free time to explore the mountains and rivers of Appalachia. We visited Ripplemead, a secluded place along the New River where the river stones are extraordinary. Cage loved the site and spent much of the afternoon enthusiastically selecting specimens of the smooth river stones. Many of the stones he admired were significantly larger than those used for the Ryoanji drawings but most of them were portable. We both realized that the larger sizes of these rounded stones might suggest their use in an experiment related to that of the Ryoanji drawings, in which he could employ a wide variety of materials, particularly brushes and water media, rather than pencils. I commented that the Ryoanji drawings suggested the possibility of a painting experiment in watercolor that might use the rocks from the site on the New River. Without dismissing the idea, he indicated that he was too unfamiliar with the medium and materials to imagine how to undertake such work – and that he felt unable to organize the studio facilities that would be necessary. His response seemed to indicate that he was being realistic but not closed to such an idea. During the next few days I resolved to try to create an appropriate studio situation in which he could acquaint himself with watercolor materials, and to surprise him with it before his departure. I returned to the site with my students and gathered many of the larger stones.

At the conclusion of his visit in 1983 Cage visited my studio, where I showed him the “studio practice” I had prepared for him the night before. It included an ample floor space covered with soft particleboard, and the 60 or so river rocks gathered the previous day and now numbered and divided into general size groups of small, medium and large. I provided a large selection of watercolor brushes each numbered and arranged in groups according to type and size, a selection of different kinds of rag papers, a palette of about 26 colors, and additional tubes of paint and many various containers for mixing paint. After a brief demonstration of brushes and paint qualities, I encouraged him to “experiment” by painting around some stones on several “practice” sheets of bond paper, which he appeared to enjoy. Then Cage took out his computer generated pages of random numbers based on the I-Ching and began to create a program for a painting – which was executed in about an hour – and I drove him to the airport for his trip back to NYC.

*

The experiment in my studio in 1983, and his ongoing development of his etchings informed and inspired his watercolor painting experiences at the Mountain Lake Workshop in 1988, 1989, and 1990. Prior to his death in August 1992, he was planning to return to Mountain Lake to make new paintings in the following October. In late 1989 I had shown Cage some examples of how the invisible divisions (or panels) that he often incorporated into his watercolors (and his composing of music) might become visible yet subtle elements of future painting experiments – his curiosity was engaged by this possibility. I believe that had he returned to the Mountain Lake Workshop in 1992, his watercolors might have expressed some correspondence with the soft geometric appearance of one of his final series of etchings at Crown Point Press, HV2 (1992).

The exhibition, John Cage: Watercolors, Selected Drawings and Prints, articulates the relationship of Cage’s watercolor paintings to his important involvement with printmaking. I think that Cage’s fourteen year-long (1978 – 1992) experience at Crown Point Press transformed our idea of the traditional discipline of etching as surely as he had reinvented our idea of music thirty years earlier. His late-career watercolor paintings demonstrate, like his graphic works, a profound sense of beauty not usually associated with Cage’s dismissal of conventional aesthetics. An intrinsic sense of beauty, in fact, is at the center of the experience that one may have in encountering his work. The watercolors shown here reveal the dynamic interaction with his graphic art works (mostly unique images) after 1988, in works such as The Missing Stone, 9 Stones, and 10 Stones– all produced 1989.

This exhibition offers an essential visual component to complement Cage’s lifelong achievement as America’s foremost avant-garde composer, and highlights his role as the principal mediator of the influence of Asian culture and philosophy on his generation and those to follow. Cage’s visual art, like his writing, brings an even wider audience to his uniquely pioneering work and contributes to a broader understanding of his strategic use of “chance operations” in his music, writing, printmaking and painting as a way to redirect our pre-conceived and authoritarian attitudes toward art and life.

NOTES:

- My visit with Cage was to interview him about the Pacific Northwest painter and mystic, Morris Graves, with whom Cage had a long friendship, whose retrospective exhibition I was organizing for the Phillips Collection. Graves and Cage became close friends in Seattle during the late 1930’s when Cage took a position as percussionist at the innovative Cornish School of Art. Graves was a colorful and pivotal figure among a small and adventurous group of young Seattle artists and involved Cage in his famous Dada antics as well as introduced him to the Buddhist Temple in the Yessler district, Asian art, and aspects of the Native American culture. The Painter Mark Tobey taught at Cornish at that time, and also became a critical figure in Cage’s artistic development and befriended the 26 year-old Cage. Our conversation that morning was filled with discussion about his deep involvement with both Graves and Tobey at a formative time in his own artistic development – and how Tobey in particular related to aspects of his current experiments in visual art. Cage described how Tobey and his paintings had profoundly effected his “seeing” – his actual perception of the world. The Phillips Collection project resulted in his traveling retrospective in 1983-84 and my publication, Morris Graves, Vision of the Inner Eye, (New York: George Braziller, 1983).

- The computer program had been developed for him at Cornell University – in order to more easily allow him to randomly access the 64 Hexagram structure of the I-Ching without having to go through the process of throwing stones or sticks. Based on our conversations, it was my impression that Cage chose the system of random-number access of the I Ching, rather than the Rand Corporation system, or any other system of random numbers, as the basis of his own use of indeterminacy in his work, because it was the most ancient system of random numbers in the world – and he wanted to point to that in a gesture of cultural affirmation of its significance – as well as acknowledge the influence of Asian culture and art on world culture. After selecting the elements of the work – or making “choices”, Cage described making Changes and Disappearances from eight copper plates that had been cut into 66 various smaller pieces whose curved shapes were determined by dropping greased string from various heights onto the plates (as an homage to Marcel Duchamp’s earlier use of a similar strategy to create “lines”) and straight edges determined by cutting along lines between chance-determined quadrants, he described how three types of etching techniques might (according to chance) be applied to these pieces, as well as photographic images of drawings from Henry David Thoreau’s journals.

My (partial) descriptions of processes and materials involved in Cage’s etchings have been derived from Crown Point Press publications documenting Cage’s work at the press, particularly, John Cage – Etchings: 1978 – 1982(Crown Point Press, 1982) containing Paul Singdahlsen’s writing about On the Surface 1980 – 1982) and Lilah Toland’s notes on Changes and Disappearances(1979 – 1982), and also Kathan Brown’s book, John Cage, Visual Art: To Sober and Quiet the Mind(San Francisco: Crown Point Press, 2000) and her writing on Where R = Ryoanji(1983). Kathan Brown’s essays on John Cage have been particularly helpful to me.

- The Ryoanji etchings consist of patterns of circular, overlapping lines incised with a sharp dry point etching tool around stones placed by chance operations on a copper plate. the size of the prints and drawings as well as the number of stones (15) that he used for their execution are proportionate with the number of stones and the space in which they are arranged within the 360 square yards of raked gravel of the Ryoanji garden. The development of these etchings preceded Cage’s ongoing series of Ryoanji drawings; both the Ryoanji etchings and drawings were made approximately during the time that Cage’s was composing the music entitled Ryoanji(1983-84); although Cage described to author Joan Retallack how the music is different from the prints and drawings, (cited in Kathan Brown, John Cage: Visual Art to To SOBER and QUIET the MIND, (San Francisco: Crown Point Pres, 2000) 96), all three creations are inspired by the Zen-style Ryoanji garden in Kyoto, Japan.

ZONE: Chelsea Center for the Arts and Guest Curator Ray Kass would like to thank Laura Kuhn, Director of the John Cage Trust, Kathan Brown, Director of the Crown Point Press, and Margarete Roeder of the Margarete Roeder Gallery.

Related:

Categories: exhibitions

Tags: John Cage